I’ve never been less than an hour early for my train. I don’t know if it comes from a sense of heightened preparedness or an ongoing current of anxiety that doesn’t even let me sleep in on weekends. Years of sitting in an airport two hours before another passenger arrived ingrained this practice into me. For so long I hated the limbo of traveling yet sitting still. I ended up counting the seconds as they strolled by to occupy my brain. I don’t mind the time now. It’s a moment to pause. It’s a moment to observe the world around me I take for granted every day.

I walked into 30th street station at 1:15pm. I gazed at arrivals from the entrance way trying to find my train to Connecticut. I took note that it was harder to read this sign now than it was last year. It seemed constantly staring at a computer screen for the last ten odd years had started to wear away at what was once 20/20. I walked towards gate three which housed tracks three and four as my Acela never left from anywhere else. That never stopped me from matching up the numbers on my ticket and the ones on the sign about twice every minute. Look down, 2170. Look up, 2170. Gate three, track four, as usual. It was 1:20 now. I had seventy minutes to kill.

I found a seat on the aged wooden benches that offered lodging to travelers much more homesick than I. I put on my headphones and tuned out the sounds of the mostly empty train station but kept my eyes alert. I watched the people around me lug around their suitcases, make phone calls breaking the news of another delay, while a man filled out some form on a clipboard. A bird had haplessly flown its way into the building. It sat a mere three feet away from me. I took out my camera, but it flew away before the lens could shutter. Almost as if it was telling me the moment was not meant to be captured. Please, I wish only to be a fleeting memory, it seemed to say to me.

The man with the clipboard now stood opposite me. Using the top of his bench as a desk. I noticed his continuous glances and wondered if he wanted me to fill out his survey or sign his petition. Whatever it was, he was furiously working away at it. He grabbed my attention with a wave of his hand and spoke. I couldn’t hear him. I took my headphones off and he repeated the words.

“Can you pull down your mask for me?”

I was confused but automatically obliged.

“Give me a smile.” He enjoined with one of his own.

I replied with a mix of confusion and amusement “Are- are you drawing me?”

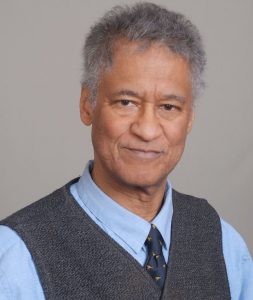

He began walking over to sit next to me and motioned for me to return my mask to my face. He sat next to me and began to tell me about himself. Well, more accurately he told me to look him up on my phone. I obliged. I typed “Irving Fields Philadelphia” into the search bar and waited for the results to load. There he was. The photos that appeared depicted him in nearly an identical outfit. The flat cap and scarf he wore perfectly fit the role of artist he was playing. His square frame glasses still hung over his nose, only helping him see the page below him and not my face. His dark skin devoid of wrinkles did not reveal his age but the rasp in his flamboyant voice and grey moustache did.

As if he was reading from a script, he began to recount his story to me, detailing the articles that appeared. He spoke in muffled words, and his story didn’t seem to come to him in chronological order. I did my best to listen carefully and closely as my eyes flickered back from him and the clock hanging on the wall. He wanted me to look at him for the drawing, but enough time had passed that fear of missing my train began to creep in.

As far as I could tell the story begins the day he was struck by a car. To put it bluntly he said the accident left him both physically and mentally fucked for a number of years. Almost to add validity to his story he lifted his left pant leg revealing his prosthetic leg.

“Say Ouch!”

“Ouch.”

Whether the medical bills or the unemployment during those dark years, he ended up living on the street. He spent a long time living without a warm place to sleep until he got an idea. He began going to the grocery store and asking women if he could draw their portrait or help them with their groceries for something to eat. No doubt the unusual nature of his request stood out to people, and he found himself with a new source of income and, more importantly, food.

“I would always ask women, and they’d say ‘well, I’m not wearing any make up’. I told them it wasn’t a picture! It made no difference to me. “

Eventually, Irving’s habitual workspace became Pat’s Cheesesteaks. In the same manner that I met him many people found themselves sitting across from a man with pencil and paper in hand sketching away asking them to hold perfectly still mid-meal. One of those subjects just so happened to be a journalist reviewing the restaurant. They began talking, having about the same conversation that I was now engaged in, only eight years earlier. By the end of the exchange Irving became a part of an article. As he told me the story, I could sense the pride and accomplishment in his words. Being written about adds legitimacy to one’s craft. I hope I’m doing the same for him here. When he asked me what I did, I told him I was a writer. I’m currently fulfilling a promise I made to him with these words.

“When I first started out, I only drew women and sometimes their boyfriends. It seemed to pay the best. But now I can draw whatever I want. Now I only draw pretty boys like yourself, but remember, I’ll always be pretty boy number one.” He joked with a level of sincerity.

The words did not really faze me as I had prepared myself for anything at that point, but I did take it as the unusual complement it was.

Being published helped him find a home, he told me. Irving continually reminded me that he used to be homeless. He wasn’t any more. I couldn’t help but feel sad about his constant reassurance, knowing how many people must have treated this incredibly friendly and eccentric man less than human. He no longer had to draw to eat, but it clearly meant a lot to him. I could tell he wanted the first word associated with him to be artist and not formally-homeless.

“I’m drawing to feed the homeless now.”

He was about to ask the question I knew was coming from the moment we began speaking. But I didn’t mind.

“Can you pay for your portrait?”

“Sure.”

“Alright, that’ll be a thousand dollars.” He laughed.

“How about twenty?” I countered.

“Yeah, alright, man. That’s beautiful, thank you.”

Art and money exchanged hands, and I saw his work for the first time.

“You like it?”

“I love it man, thank you.”

“Give it to somebody you love. And tell them they’re beautiful.”

“I’m going home right now. I will.”

An hour had blown by, and it was time for me to board.

“You know, before he wrote that article about me, I had no idea Philly was known for cheesesteaks, and I’ve lived here my whole life.”

I laughed and thanked him for making my wait infinitely more entertaining. I won’t lie. The likeness isn’t exact. But I really do love the drawing. I’d like to think the portrait was free, and I paid him for the story. I suppose, that’s why I always show up early.

Drew Kolenik is a creative writing student at Temple University. Since a young age, he has always had his hand in one creative endeavor or another. He has taken his passion for story-telling and daily journaling to begin the search for his audience.