I mourn two feet of hair so I arrange ragweed

in a halo until I start sneezing. Sometimes I call

myself Bulb Queen, sovereign burr-catcher,

playing house in the phlox like a big girl.

Sunlight arrives on Earth at 100 decibels

but still slips through spring leaves silent.

There’s a chalk line around a corpse

in my yard that still hasn’t been identified.

There’s a seed pod too, hanging from a sprout

and it’s probably better I lost sight of it

or I might have wanted to pluck it again.

Would you believe me if I told you that

daddy long legs aren’t spiders? Don’t ask

me what they are because I might say aphids,

round in the center, wreathed in knees, could

spin in a circle without moving their head.

If I thought I could stand the tickling I would

smear my scalp opilionid, something finally

living, ouroboros as head eating leg eating leg

eating leg. I don’t need to be a spider. Anything

can throw a web even without silk glands, even

if tripping over joints and wayward grasses seems

like the only thing left to do. I could cocoon

if I wanted. I could suck the water from my chest

until I’m nothing but leg. I could eat my skin,

huskicide, dry like irises once bulbous, now

crisped in the shape of paper-thin wings,

translucent. I could dehydrate, too.

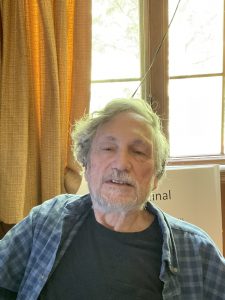

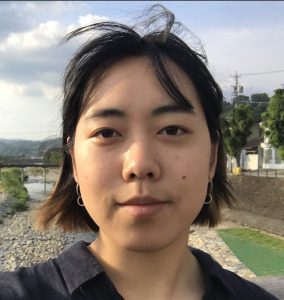

Dina Folgia is an MFA candidate at Virginia Commonwealth University. She was an honorable mention for the 2021 Penrose Poetry Prize, and a 2020 AWP Intro Journals Project nominee. Her Her work, which has been nominated for Best of the Net and the AWP Intro Journals Project, has appeared in Ninth Letter, Dunes Review, Stonecoast Review, Sidereal Magazine, Kissing Dynamite Poetry, and others. She is a poetry reader for Blackbird and Storm Cellar. Keep up with her work at https://dinafolgia.com/