WINNER OF THE 2019 SANDY CRIMMINS

NATIONAL PRIZE IN POETRY

Elegy For Breath

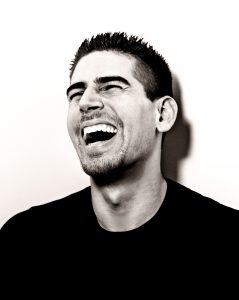

by Carlos Andres Gomez

Picture the adolescent: mimicking

what makes him worthy. Pick his

most potent snapshot for click-

bait: fresh-faced but mean-

mugging; same mask I’d pull

clean across my jaw for any

Polaroid of me & my best friend

in eighth grade. Let’s be clear: joke

stance—now used to justify

killing make just the just-

snuffed, just clumsy youth branded

bold-fonted & blood thirst. Peace

sign transmogrified to gang sign—

since the expert talking head

confirmed it. The expert talks &

confirms inside a rectangular frame

that renders most of him invisible.

Talks & confirms two bullet-

points from the bleached-

teeth interviewer. But nowhere

is the testimony of breath

stifled, the practiced hands that

remained watched whenever they

ascended, whether in prayer or

surrender, holding a bag of groceries,

a cell phone, or a son. Nowhere

is that last sigh freed from his tired

lungs as the sixth shot struck

the base of his skull sprinting

with back turned. The neighbor describes

that final sound I did not hear & yet

cannot unhear. It is suddenly the last

sound I hear from too many people

I love: my brother-in-law, my four

nephews, my high school best friend,

my infant son. (Every police officer

is out in the world defending

himself. Every one of them describes

the nightmares in which they see

a dark object against the darkness

that turns into fire & populates a rigid

void with lead. Every police officer

is a human being. He makes mistakes

sometimes. He got nervous. He thought

about his two kids & his pregnant wife,

it was fourteen days before retirement.

He’s never missed a Sunday at church.

Believe me, it’s true. I’ve seen him pass

the donation plate. Sometimes

he takes a naked, crumpled bill in his

calloused hands, wipes the sweat

& residue on his crotch.) I saw Jesus

on Easter Sunday still resting

on the wall, a hooded sweatshirt

draped across his torso from the college

he was to attend just to make it all a bit

more decent. Everything you stare into

becomes a fist, a loaded weapon aimed

at your face. I wake up in a country

based on a single document made

to protect every human being equally

who is a wealthy, white man. The woman

I meet after my show in Myrtle Beach,

South Carolina has no response when

I ask her why the killing of three dogs

made her protest, made her write letters,

made her boycott, while the murder

of a defenseless Black child inspired

not a single word from her lips?

Loud music; blocking the middle of an empty

residential street; a wallet in a trembling,

outstretched palm; a back sprinting away

in fear; a woman after a car accident

knocking on a door for help; a toy

rifle in a Walmart in Ohio; a boy

in Money, Mississippi, walking, lost

in thought, a stutter from Polio, a whistle

he learned to cope with his stammer,

when the implication of Blackness

is always absolution from murder.

My son’s first breath was with-

held: the cord that had nourished him

for nine months now choked three

times around his throat, as he fought

for life. Like his sister at birth. Like

the father on a sidewalk in Staten

selling cigarettes to support his six kids

to survive born fighting stayed fighting

to breathe. When my son gasped

finally & then slumbered into dream,

his blooming tenderness unguarded as

a single orchid, I said a silent prayer

for the imagined crimes his world was busy

inventing, to condemn him for being born

Black & having the courage to breathe.

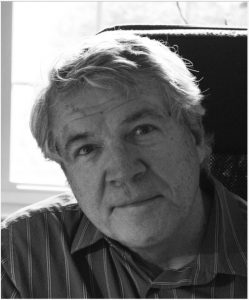

Carlos Andrés Gómez is a Colombian American poet and the author of Hijito, selected by Eduardo C. Corral as the winner of the 2018 Broken River Prize. Winner of the 2018 Atlanta Review International Poetry Prize, 2018 Sequestrum Editor’s Reprint Award in Poetry, 2015 Lucille Clifton Poetry Prize, and a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee, his work has appeared or is forthcoming in the North American Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Yale Review, BuzzFeed Reader, Rattle, CHORUS: A Literary Mixtape (Simon & Schuster, 2012), and elsewhere. For more, please visit: CarlosLive.com.