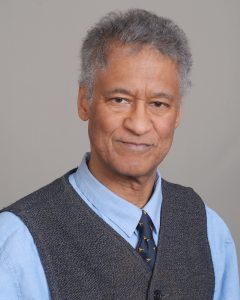

Shannon Frost Greenstein is the author of “These Are a Few of My Least Favorite Things,” a full-length collection of poetry from Really Serious Literature, and “Pray for Us Sinners,” a short story collection by Alien Buddha Press.Shannon’s work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in McSweeneys Internet Tendency, Pithead Chapel, Bending Genres, Philadelphia Stories, X-Ray Lit Mag, Reckon Review, Arkana Mag, New Mexico Review, Epoch Press, Feral: A Journal of Poetry and Art, Cabinet of Heed, Door Is a Jar, STORGY Lit Mag, Lunate Fiction, Ellipsis Zine, Scary Mommy, Crab Fat Magazine, Bone & Ink Lit Zine, Ghost City Review, trampset, Crepe and Penn, Spelk Fiction, Rhythm & Bones Lit Mag, Blunt Moms, the Philadelphia City Paper, WHYY, The Manifest-Station, Royal Rose Magazine, and elsewhere.She harbors an unhealthy interest in Hamilton, Nietzsche, Mount Everest, ballet, and the Summer Olympics. Shannon aims to write The Next Great American Novel while simultaneously acquiring more cats.

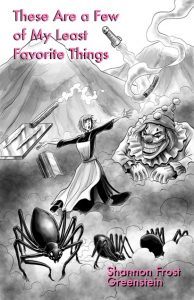

Review of Shannon Frost Greenstein, These Are a Few of My Least Favorite Things

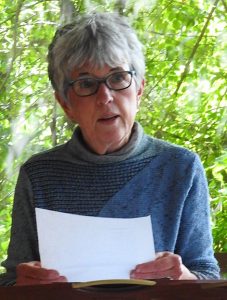

by Sarah Van Clef

When I read the collection of poems “These are a Few of My Least Favorite Things” by Shannon Frost-Greenstein, the first word that came to mind was balance. How does one balance the wickedness of the world, the unfortunate changes and shifts we see in our cultural society, mental illness, drug addictions and illnesses, and the beauties of the world and culture like friendship, companionship, and family? In this collection of poems, Frost-Greenstein walks on the tightrope of such balances. She provides readers with a dialectical lens of the analysis of what suffering and life and celebration and horror actually mean to her. She culminates in the love of her world around her amidst the destruction that is going on in and outside of her mind.

From the beginning of the collection, in her poem “Down To The Filter”, Frost-Greenstein owns the fact that she “backslid today”(Pg. 8) amidst her many roles of being a mother, a writer, and a basic functioning member of society. Like so many of us do when trying to tackle any kind of demons we may be facing, “Down To The Filter” provides such agency that we are all allowed to “smoke that bitch down to the filter” (pg.9) when we need to, that as human beings, we are allowed to slide back into old habits and routines that sometimes aren’t the healthiest for us mentally. By the end of this poem, Frost-Greenstein boils it down to one thing: She is human, and humans are not always perfect, and neither are the demons that lurk in this collection.

In this collection, Frost-Greenstein not only tackles hard subjects like drug addiction and family trauma, she also widens the dialectical lens and looks at her city of Philadelphia, and the violence and destruction that was once her home. With an apocalyptic tone, Frost-Greenstein describes the violent segregation in her society in her powerful poems “The White Pieces Go First”, and “Billy Nair’s On The Moon”. For the speaker in these poems, she must ask herself a larger question: What does home mean amongst the chaos? For Frost-Greenstein, she finds the answer in her children, her trauma, and her voice.

These poems are a call to warning, a loud, scream and cry for help. Not only does Frost-Greenstein understand that these poems need to be written for the mothers, fathers, friends, and neighbors that have felt similar loss and grieving, but also the future generations of leaders and artists that can change the narrative in how we look at mental illness, drug addiction, and familial trauma. Poems don’t always have to be pretty, and in this collection they weren’t in the slightest, but as much as it was difficult to read contextually, it surmounted in its beauty between the lines. Powerful in their own right, “These Are A Few Of My Least Favorite Things” is a collection that needs to be read, screamed, and chanted to anyone who will listen because this is how change actually comes to fruition.

Sarah Van Clef is a poet and memoirist from South Amboy, New Jersey. Her lyrical essays and poems have been featured in Local Gems NJ Bards Literary Anthology, The Monmouth Review, and others. She currently is the Reviews Editor for Philadelphia Stories, An Adjunct Professor at Monmouth University, and the Co-founder of 2nd Renaissance Arts; an online creative cohort for writers to network and celebrate writing through educational and enrichment programming. Sarah holds an MA in English Writing Studies from Monmouth University and is currently working towards her MFA in Creative Writing. When Sarah is not teaching or writing, you can mostly find her on the beaches of the Jersey Shore or singing in her band, The Cellar Dwellers.