Within the salon’s dark cough, beauticians

glue fingernails to their anchorage.

Enslavement to labor is nothing like sleep.

Awake they wait for papers whose likelihood

is quantum mechanical. They consume, pay

taxes on tobacco and tea, and move through

a city as though stickless in a kennel

of unfamiliar dogs. Where they were born

they welcomed eggs without salmonella.

Extractive industry propelled a century

of blackened air. At night they could feel

atmospheric mud and the breath of siblings.

And into the night they would evacuate

to flee the earth’s hand-wringing. Here, they

subsist on a translated diet. They must train

the tongue backward and learn to swim

through natives’ suspicion. Headlong, they plunge

into the mainstream with so much fervor, so little rest.

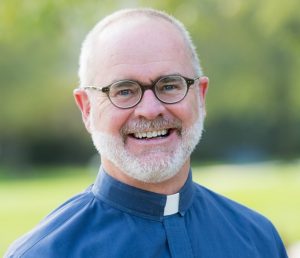

Alan Elyshevitz retired as an assistant professor of English from the Community College of Philadelphia. He is the author of a collection of stories, The Widows and Orphans Fund (SFA Press), a poetry collection, Generous Peril (Cyberwit), and five poetry chapbooks. Winner of the James Hearst Poetry Prize from North American Review, he is a two-time recipient of a fellowship in fiction writing from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts.