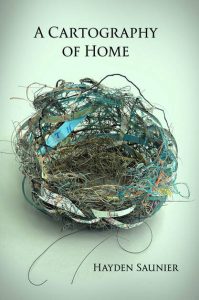

Saunier, Hayden. A Cartography of Home. Terrapin, 2021.

Hayden Saunier’s A Cartography of Home (published in February by Terrapin Books) is another breathtaking example of what this poet does best: crafting sensuous language, weaving together word play and close observation. Saunier is like an accomplished oil painter at work with a palette knife. Although we know the shape of the instrument—her work is informed by traditional poetic forms, especially the couplet’s mirroring march—we are still surprised by the deftness of her strokes (the linebreaks that sing) and the vibrant colors of her language. There is an urgency to how Saunier uses time as a lens for looking at the natural world that is poignant and direct without ever tipping too far over into sentimentality.

Saunier can skirt the edge of a careworn metaphor. As one example, the title poem examines the speaker’s relationship with her mother as a map. It might have been easy to rely on trite comparisons like being “pointed the right way” and “sailing through storms,” but Saunier uses the language of discovery and exploration, and yes, cartography, to mourn the passing of the matriarch and the unmarked journey that is ‘matresence’ (a word that recently has gained media attention, meaning “mother-becoming”). She writes, “My mother was a place. She was the where/from which I rose. …as I grew into my own wild country” (Saunier, lines 1-4). The artistry of Saunier’s work is that she translates universal human experiences while still managing to make them feel intimate. It is like looking through both ends of the telescope at the same time. This is a speaker who does not directly reveal a lot about herself, and yet, she admits that, for her mother, “Monsters mark the desert blanks on her charts too” (line 15).

This work looks outward toward the natural world to earn the poems’ resolutions. In some cases, it happens in the final lines that tie back to the title (as in, “I’m Also the Fox”) or a voice that turns toward the reader as if she stands on a dark stage to stage-whisper, “Oh, you didn’t think/there was a catch?/There’s always a catch.” (“Gathering Black Locust Blooms,” lines 26-28). The underlying architecture of Saunier’s work is hard wrought, and like a Swiss watch or hand-forged lock (see the poem “Locks” for more on what this costs), the impressive beauty of its intricacies is that they remain invisible. And yet, her work can be wryly humorous, and I hope I will be forgiven for comparing it to the carrion bird, whom she hallows in her poem “Evening View with a Turkey Vulture”: it is the “cathartes aura/golden purifier/[who may be] beak-and-talon-tired/from a long day’s taking up of the dead” (lines 17-20). These are poems to be enjoyed for what they are doing, how they shift the reader’s attention to splendor and the fading art of really looking at the world around us.