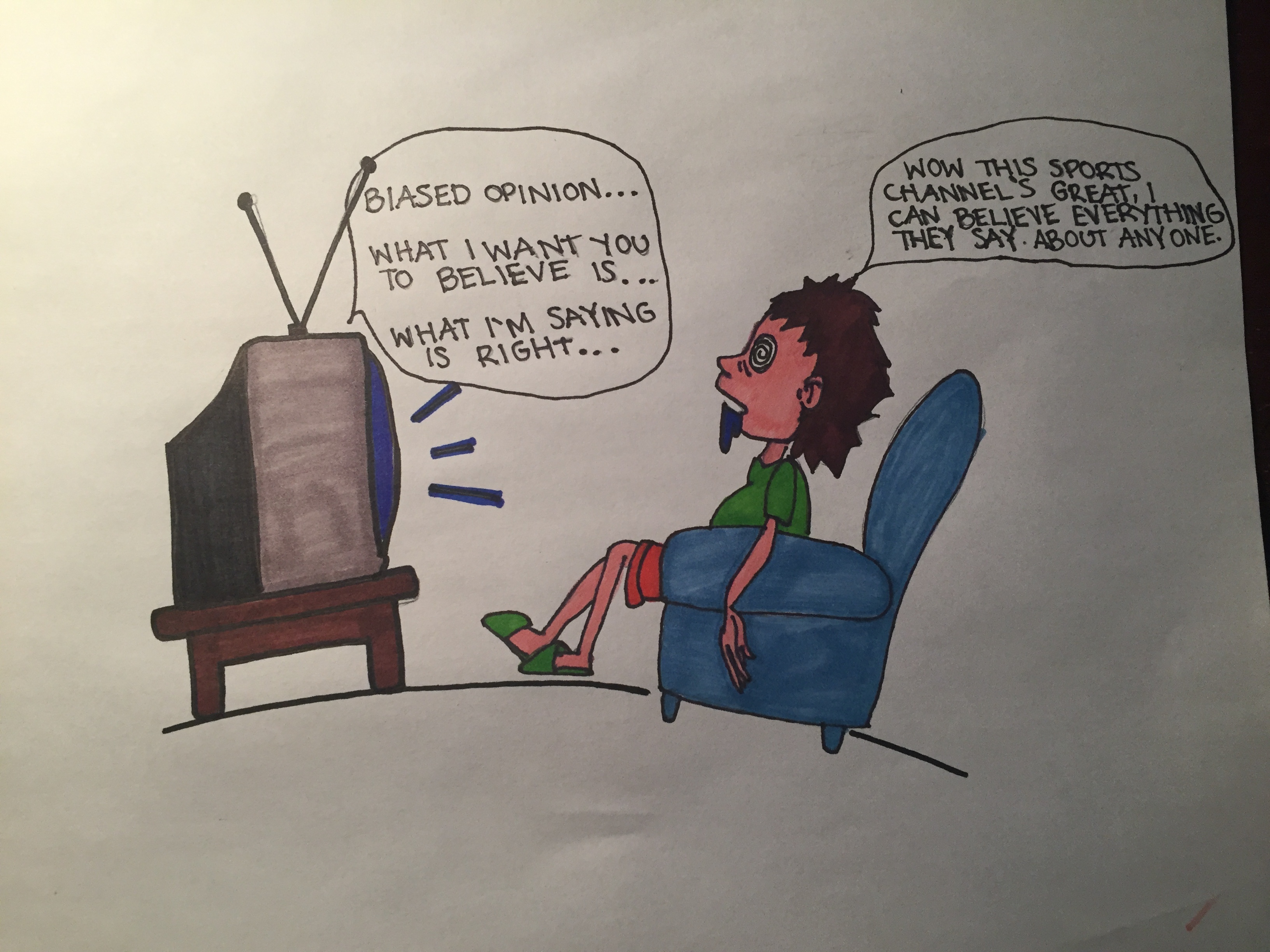

Alexandra Murray is eight years old and in the second grade. She likes to read, write, and draw. She enjoys reading the Warriors series and playing Minecraft with her sister, Scarlett. Her jingle is a spoof on the song, Mr. Grinch, and is paired with her drawing of her family’s dog, Whisky. Alexandra produced these pieces at the Free Library of Philadelphia’s 2017 Comic Con event.