She was a fast learner, an easy learner, therefore, a joy. She could be counted on, never late, sitting front row, her hair twisted twice, pulled and bound by a ribbon. She wore cream-colored sweaters, white blouses on very warm days. She was one of those rare visions: a freshman who’d taken cues from re-runs of Gidget or The Patty Duke Show and set about fashioning the exact college experience she had planned.

When he unbuttoned his sport coat before her or rocked on the balls of his feet and surveyed the rest of the class, his eyes finding hers, he was moved. He’d known other eager students who could toss back answers as if they’d studied the whole night before to please him. These students went on to respectable programs at respectable schools. Yet watching Rose-Lynn Coyle, listening to her read the work of Dryden, Pope, and Gray, how her voice would lilt at a surprising turn of phrase and sometimes laugh, Randall felt lifted, reminded of why he was a scholar, why knowledge and pursuit of knowledge had been and still were so very important to him.

One morning he asked to speak to her after class. His voice wavered, an embarrassing quality he thought had vanished with his youth. “Marvelous insight today,” he said. “The Rape of the Lock is nearly as sad as it is funny. That’s why we read it as a mock epic.”

“I wondered if I was reading it correctly,” Rose-Lynn said.

She was very small. He’d never stood close enough to realize how small, in fact, she was. “Are you thinking of graduate school?”

“Oh, I think about a lot of things.”

“Start planning,” Randall said. “Never too soon. You have something. A fire.”

“To be honest,” said Rose-Lynn, “your class is the only class I’ve been doing well in.”

He looked at her and smiled. She was wanting to say something more, he felt it, too. He watched her search for the words.

There were times when Randall took his good position in the department for granted. He—along with Merritt, Chouinard, and Wester—was branded one of “the senior statesmen,” a term reflecting the years he’d spent with the department, a term he didn’t care for. He was fifty-two, not particularly old. He had a full head of hair. Half the men in the department, years younger, couldn’t boast that. No lung cancer to complain of, as Chouinard did, often so busy he’d forget to eat yet never too busy for a smoke. Merritt, however, ate like a horse; his clothes stretched at the seams. And Wester, the oldest of the four, slowly, year to year, was losing his mind. Students complained of his incoherent lectures.

The English department, often thought of as “liberal,” was not a place of change. While the rest of the college grasped at modernization and physical reconstruction, English Hall remained true, was filled with dust motes and smelled old, like a place of learning. Sometimes, descending the main flight of stairs, Randall’s eyes would tear, considering the knowledge dispersed among the walls. What changes that did occur within the department were small ones, visiting lecturers, a revision of the previous year’s syllabus. There was a push to move more and more to the Internet, an experiment Randall had questioned initially but was nonetheless supportive of. John Goodwin, the new Romantics expert, had argued in favor of it.

Randall wasn’t sure of his feelings for John Goodwin. Goodwin was with the department only three years, the type of fellow one liked in order to forego the guilt of disliking. For an academic, John Goodwin was striking, with his big frame and dramatic voice and the beard he kept trimmed close, his eyes that always seemed caught up in clouds. Goodwin worked out four times a week. His criticism was sound. Randall had read each of his books, trying to find some small thing not to like about John Goodwin, but as he read Goodwin’s books, Randall could hear that booming assured voice, the voice that made everyone around him feel welcomed and wanted and at ease. No one denied the rumors about John Goodwin and his relationships with select students. But these types of things weren’t uncommon. Administrators spent salaries arguing the implications of such trysts, yet no written law—in the College Code or otherwise—prohibited them once a class was over. Those involved in such things did their best to keep hush. Whatever happened within the walls of English Hall didn’t escape those old walls, and what happened beyond the walls was under no one’s jurisdiction.

A relationship with a student had never, really, crossed Randall’s mind. He was married for twenty-four years, with two successful grown children, and in the scope of his own life, he thought himself a success. Everything he wanted, he had: a five-bedroom house with a clay tennis court, one grandchild, a cocker spaniel that retrieved the stick thrown for its amusement. Randall’s job with the college was secure. One night, walking home from a snack at the town restaurant, he’d turned to his wife, taking her hand that was cold from the snow. That night, there were buckets of stars, and as he looked down Main Street, he could see the gray of the Schuylkill, the black blocks of college buildings beyond. “This is all I’ve ever wanted,” he said to Lois, and she agreed. They hurried home. He poured brandy. They sat by the fire listening to Scarlatti until a log shifted in the fireplace. In a trance, they rose together. It was time to sleep.

Rose-Lynn appeared at his office hours, tapping at his door, until he told her that 3:30 every Wednesday afternoon would be the perfect time for them to meet. He’d make no other arrangements, that slot was for her and her only. “How do you like that?” he said.

He didn’t mind looking at the essays she brought from other classes. “I’ve put my whole soul into this one,” she insisted, “but still it doesn’t seem good enough.” He tried to show her where points trailed off, where her interpretation was faulty. “Write down exactly what you just said, it’s so good,” she told him. He recommended books she might turn to, important articles only a scholar would know existed.

One Wednesday afternoon, Rose-Lynn was in a state. “Professor Malvin hates me,” Rose-Lynn said. “She absolutely hates me.”

Malvin was not Randall’s favorite person. Students called her “The Vampire” because she’d written three books on those blood-suckers, one book on blood-letting, and three others on Victorian women and rape fantasies. Malvin always wore black, and her long hair seemed a shade even darker. Some joked that she was a witch, was good friends with Anne Rice. Some said she was Anne Rice. Of all the women in the department, Dorothy Malvin was the only one Randall would call a true feminist.

“She hates me because I’m pretty,” Rose-Lynn said. Randall had heard of cases like this, cases where Malvin favored fat girls, ugly girls, lesbians. “I turned in this paper, on time and everything, and still she gave me a C-.”

“A C-? That seems very low for your work.”

“She hates me. There’s nothing I can do.”

“Let me see the paper.” Malvin had scrawled red pen everywhere, the paper a bloody mess, an effect he was sure she intended. Malvin’s comments seemed reasonable, however; the paper did lack organization, showed no central thesis.

“I can see why you think she hates you,” Randall said. “Let’s you and I hate her back. Together.”

As Rose-Lynn reached for her essay, the tip of her fingernail dragged across Randall’s bare wrist, so slowly he thought it couldn’t be accidental, that slight but deliberate weight awakening his skin.

The last week of April, Randall found an invitation to John Goodwin’s 3rd Annual Bacchanalia stuffed into his department mailbox. Since Goodwin’s first term at the college, he’d been running the event, a party for faculty and the English majors held at his own home. The night was intended to be one of literary revelry. “Come as your favorite Romantic,” the invitation said. Randall had never previously considered attending one of Goodwin’s Bacchanalias, having heard that those department members who attended always left by nine. What happened after that, Randall could only guess. After Bacchanalia weekend, students in his Monday morning class looked exhausted, as if their lives had been spent.

“I received your invitation,” Randall said, passing Goodwin in the hall.

“You’ll be coming, will you?” said Goodwin. Randall knew Rose-Lynn had been a student of Goodwin’s, his class another of her trouble classes and Goodwin another professor who had her all wrong.

“Yes, maybe yes, I’ll come this year. I’ve heard good things.”

“The wine will flow freely for those of age.”

“And what will the children drink?”

“Blood,” Goodwin laughed. “Or Arizona Iced Tea. I hear it’s a hit with the younger set.”

Goodwin tapped down the hall into the department office. Randall was laughing, he didn’t know why or how, but the sound echoed up the stairs to the marble mural of Shakespeare. Then English Hall went silent.

“Aren’t you going to shave?” Lois asked.

“No,” Randall said. “Not tonight. I thought in the morning.”

“You look like an old bear.”

“I’ll be home before you know it.”

“I don’t like it when you leave,” Lois said.

“I won’t be long.”

“Here,” Lois said, searching the dresser drawer. “Even if you hate the idea of wearing a costume, at least try color.” She’d found a pink Hermes scarf with gold paisleys and tucked it into the pocket of his gray blazer. “Perfect.”

Goodwin’s place was two towns over, back from the main road, squared off by woods and cornfields with a windmill turning against the night. The house itself was three stories, a fine old structure with a balcony and a large tractor shed that was empty of tractors. He told Randall once how he’d bargained with the farmer to get this piece of land so private, just a flicker to anyone passing by along the main road.

Low music rumbled from the house, and once inside, Randall stood for a moment by the door. No one seemed to notice him. He went into a large room adjacent to the foyer, a sitting room. Candles, thin and thick, jutted from candelabras placed in the corners of the room, on windowsills, in sconces. Chairs, none matching in style, looked arranged by a madman about the large room. Boys and girls were done up as fairies, small nylon wings pinned to their backs, their faces painted pink and yellow and putrid green. He was sure the students had A Midsummer Night’s Dream in mind and wanted to tell them they were wrong: Shakespeare was Renaissance, not Romantic. There were courtiers and wenches, damsels, rakes, their faces vigorous, blushed with life. Two boys wore togas, Aristotles or Platos perhaps, a handful of Bacchae, someone as Mark Twain. Randall felt sick, lost in time, these literary histories were so crossed.

A few colleagues had arrived: Wester and Chouinard standing by the food table, the two of them done up, looking more like pimps or old nightmares than revelers. Dorothy Malvin was stationed by a window. She looked like herself, and Randall thought he’d ask her later who she’d come as, La Belle Dame sans Merci? Pouring red wine, hearty Goodwin chatted with Wester and Chouinard. Clearly Goodwin invested in his costume; the velvet and red tunic, much like a bathrobe, looked too good on him. He wore white leggings and his shirt was open at his chest. He caught sight of Randall and waved, coming toward him with a limp and carrying two glasses of wine.

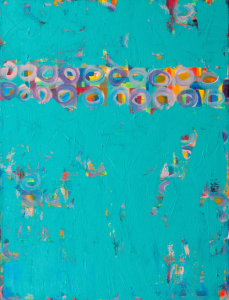

Lonaconing Windows by Eric Loken

“Professor Turner, I see you came as a businessman,” Goodwin said.

“My fancy pants are at the cleaners. What happened to your leg?”

Goodwin bowed. “George Gordon, sir. Lord Byron.” Goodwin lifted the hem of his robe and showed a grotesquerie made to look like a club-foot. “It’s a killer with the ladies.”

“I bet it is,” said Randall. He wanted to say, “And the gents, too,” seeing as Byron was more noteworthy for his bisexuality than his poetry.

“Drink this glass of wine and get yourself another.”

“I will, I will,” said Randall.

“The masses await. But we’ll talk later, once things are up and running.” Goodwin crossed the room, patting students on their backs, rustling their hair as if they were infants, his children. Randall nodded to Malvin on the other side of the room, where she feigned interest in something caught under her pinky nail.

Several of Randall’s students chimed, “Hello,” in passing, then giggled. Out of context, students transformed into creatures other than the selves he knew in class. They became chaotic and careless, infantile. He had liked every single one of his students, but he often wondered if he’d met them some other way whether or not he would have cared for many of them at all. A number of them were drinking wine. Maybe they were seniors, which was possible. Seniors would be of legal age. He looked for Wester and Chouinard, but they’d left the room. Diana Regan and Tom Voll, the two glib Americanists, lounged in chairs by the fireplace. They seemed too interested in one another. There was really nowhere else to go, so Randall sucked in his breath.

“And who have you two come as?” Randall asked.

“Percy Shelley,” Voll said.

“Mary Shelley,” said Regan.

“How nice. The Shelleys. Not going to run off together, are you?” They looked at each other, smiled. The affection the two shared for one another, despite each being otherwise married, was far from private.

“We’ll see how the evening goes,” Regan said.

“Yes, we’ll see,” said Voll. “Never can tell.”

There was a trumpet blast, a silly thing pumped through the speakers. Goodwin was standing on a stool. “I’d like to welcome everyone to the 3rd Annual Bacchanalia. Or as you few repeat performers might know it, ‘A Dip in the Drink.’ I thought we’d start our evening with some grand verse and some grand meter. Let’s hear some odes, some ottava rima, two or three bout-rimés.”

A girl in a carnation gown and dark hair raised her hand. “Okay,” Goodwin said. “We’ll begin with our Claire Clairmont.”

This Claire climbed onto the foot-stool, looking pale and ghostly. “I dreamed my life was like a leaf / half-turned, then turned in full, tossed by the Wind / the evil Wind who frets the threads of fragile life / that laughing Wind who….”

Randall had never been turned on to student poetry, by struggling poetry of any sort. The Writing Department, the small and little thought of annex below English Hall stairs, was an assault to the greats: thinking that something like writing poetry could be taught!

Yet no sign of Rose-Lynn. He poured himself more wine. Mark Twain was reading now, a kid with a high forehead, Edward something. “Great minds have fallen and no fall is greater than mine / for it was I, Adam, father of humankind….” Nothing made sense, their mixing of historical and classical allusions, not following through with metaphors. Goodwin was sure to jump up after each one, clapping, rousing everyone to a cheer, no matter how bad the poem or how silent and disinterested the crowd. As he drank more wine, Randall had the sense these Romantic attempts at poetry might become easier to stomach.

It occurred to him that he’d like to see the rest of the house, so he slipped along the wall, back to the foyer and through the rooms on the first floor. Doing all the renovation himself, Goodwin had managed. There were no smudges along the ceilings, no signs of haste. Randall padded up the stairs to the second story, past one room that was being done-over; a belt-sander, sawhorses and paintbrushes littered the floor. He passed another room yet to be touched, then he came to what must’ve been Goodwin’s bedroom, not at all what Randall had imagined. There was no Gothic bedframe with white sheets and red satin pillows, no cherry oak furniture so rich and seductively dark. Heavy drapes didn’t obscure the windows. Instead, thin white curtains were pulled to one side. The bed sheets were gray and light blue and white, a simple country motif, and the furniture that squatted about the room was rustic to be sure, certainly not horrifyingly old, nothing European or imported, only a dresser and bedside table and lumpy green chair that looked as if they’d been garnered at some Sunday swap meet.

Was this the kind of person Goodwin was in his private life, soft and quiet, someone other than his self? Randall moved about the room, touching things, picking up a small bronzed baseball, horse-head bookends, a picture of two old women in a frame. He opened the top drawer of the dresser bureau: boring white underwear, just like he had at home, rolled into balls, stuffed among socks. He felt beneath Goodwin’s clothing. Surely that was where people hid the things they feared others would find. His fingers grasped at the glossy pages of a magazine. Pornography, he thought, but was disappointed when the shiny publication was nothing more than an Alumni magazine from Yale. Randall sat down on the edge of the bed, placed his wineglass on the nightstand and began looking through its drawers: green ear-muffs, a ruler, envelopes, pencils and pens, a Bible, a book on meditation, a novelty back-scratcher. Not even so much as one prophylactic: how very boring.

Then Randall heard voices in the hall, a high-pitched giggle, followed by footsteps. He knocked over his wineglass, red wine onto the beige rug, and ducked into the bedroom closet, leaving the door open slightly with a view of the room. At first, he thought he was about to witness something important. He imagined Goodwin, sweeping away one of the girls, carrying her like property up the hall stairs and tossing her down on the tidy bed. Yet it wasn’t Goodwin, not even someone half as interesting as Goodwin, some kid with longish hair and a soul patch, dressed as Puck, half-goat, half man, with nubbins of horns stuck to his head. The girl, Randall recognized. Kimberly or Kimmy. Or was it Kimbi? Kimi? She at least looked more of the period, not some fairy creature but voluptuous and indulgent, certainly Romantic. He’d noticed her before, once at school, at the vending machine.

The silly boy lay back on the bed. Watching, Randall was certainly aroused. He could tell both were not good kissers, more motion than technique. A sliver of saliva sparkled on the girl’s lips. Then, suddenly, the two burst into laughter and stopped. The girl straightened her gold hair ornament and went flitting into the hall. “Kimberlyn,” the boy called, but she didn’t come back. “Fuck,” the boy said, getting up from the bed.

When they’d gone, Randall slipped from the closet, into the hall, pretended to be casually descending the stair, and found more red wine. Lois didn’t allow him to drink much anymore—had reason to dislike his having too much—but she wasn’t here. The readings had come to an end. Popular music played, and the fairies were dancing. Light flickered on, then off, then on. Randall thought about that girl’s mouth, that geometry of saliva descending from her lips. He could no longer remember what it felt like: kissing young lips. He’d come to love Lois and her mouth, her kiss, yet he couldn’t remember what her lips felt like when they were young. The knowledge he once ardently possessed now escaped him.

Randall’s heart leapt: Rose-Lynn! She was so carefully articulated, her hair pinned and neat, suggestively pure, not sopping with sexuality. Over the years, students like that Randall had admired for their virtues and soon forgotten. Rose-Lynn, however, was art. Forging his way through the shaky undergraduates on the dance floor, he noticed the sprig of purple nightshade Rose-Lynn had secured with a barrette and the dark eyeliner that gave her the quality of the dead. She wore ballet shoes. He noticed too, unfortunately, she was laughing and in conversation with Dorothy Malvin.

“Rose-Lynn,” Randall said. “Rose-Lynn, who . . . who have you come as?”

“Oh, Professor Turner,” she said. “I’ll let you guess.”

“You get three chances,” interjected Malvin.

“Only three?”

“Here,” Rose-Lynn said. “I’ll give you a hint.” She closed her eyes and extended her arms in front of her. “Think somnambulist.”

“Just as I thought. Coleridge’s Christabel.”

“I suggested the costume,” said Malvin.

“Who have you come as, Professor Turner?” asked Rose-Lynn.

“Oh, don’t you recognize him, Rose-Lynn? He’s come as himself.”

“What better way to appear than as one’s self,” Randall laughed. “You can insist on being nasty, Dorothy, but I’ll remind you that you haven’t procured my promotion vote yet.”

“What’s one vote?” said Malvin.

“Lovers’ quarrel?” Rose-Lynn laughed.

“No love lost,” said Malvin.

“I’m sorry, Professor Turner, Professor Malvin, excuse me.”

Randall watched Rose-Lynn go, left standing with Malvin who too was watching Rose-Lynn go, slipping through the crowd like a breeze through a dream. Malvin was silent. Randall took a gulp of red wine.

“I like you, Dottie. You know, I really do.”

“I thrive in negative space,” she declared. “Sticks and stones.”

They didn’t say anything to one another after that. He waited for her to move away from him, and when she had, as he was sure she would, without another insult or an apology, he went to look for Rose-Lynn.

He discovered Rose-Lynn between the legs of a boy Greg on Goodwin’s back porch. The boy, perched on the railing, had crossed his heels behind Rose-Lynn’s knees. Rose-Lynn stiffened, seeing Randall there, and whispered into the boy’s ear.

“Let’s go for a walk, Professor Turner,” Rose-Lynn said.

“Yes,” Randall said. “Let’s.”

The backyard was nearly the color of dark wine now, the perimeters of each shadow red-tinged. Rose-Lynn pointed toward a cluster of trees at the end of the lawn.

“That boy’s just a tadpole!” Randall said.

“I knew you’d be jealous,” said Rose-Lynn. The trees at the end of the yard were arranged in a circle, a faerie ring, and at its center Goodwin had placed a cast-iron bench. Black roses twisted around one another, serving as legs. “Where’s your wife?”

“She hates these things.”

“I imagine her thin, old and pale,” Rose-Lynn said.

“She’s not so old or so pale. How old you do you think I am?”

“Fifty,” she said. “Fifty-two?”

“I was hoping you’d say forty.”

“You asked me how old I thought you were, not how old I thought you looked.”

“Ah. You seem older tonight,” Randall said.

“I’m an old soul.”

He could detect something in her eyes, a self-immolating fire, something that both excited and disturbed him. “Who are you?” he asked.

“I’m Rose-Lynn, silly. Who else would I be?”

“Some kind of bewitchment,” Randall said. “A snare.”

“You’re caught up in the night.”

“How can I not be?”

“Do you have any children?”

“Two: one son, one daughter,” Randall said, and then joked, “Do you?”

“No,” said Rose-Lynn. “I was pregnant once, abortion, etcetera. It wasn’t a big deal, just one of those things that gets in the way.”

“In the way of what?”

“In the way of everything. Nights make me think of children, I guess. The running around, the squeals as the sun sets. When I was little we played Haunted House outside in the yard, blankets thrown over lawn chairs. I could make the scariest faces.” Rose-Lynn screwed up her face, her eyes crossed, cheeks stretched. “I wasn’t afraid like other girls.”

“My children did the same.”

“I would’ve liked you as a child,” Rose-Lynn said.

“I would’ve liked you, too, but not in the same way as I do.”

“Let me get us another drink,” said Rose-Lynn. When she walked off, Randall worried she might not come back. He’d been left at parties by attractive women before. Sometimes he wondered if that was why he’d married Lois at such a young age when other choices might have presented themselves. Too quick to get everything right, to have everything in place.

Rose-Lynn returned with a red cup. “Here.”

“What’s this?” Randall said. “It tastes awful?”

“Cheap rum.”

“An odd after-taste.”

“Oh, that’s the roofies,” she laughed. “Drink it. I mixed it myself.”

“Really now?”

“It’s my second major.”

Randall chuckled and paused. “Do you have a boyfriend?”

“Who has time?”

“And Greg?”

“I love the gray of your hair, Professor Taylor. One of the few good things about getting older. Can I touch it?”

“Sure.”

She didn’t run her fingers through it as he wanted her to; instead, she stroked his head as if she were petting a cat. The motion made him feel suddenly woozy, and he found that he was willing to tell her everything: his impressions of the other students, the faculty, the college. “You’ve awakened something in me. Kindred spirits, you and I.”

“I should get to know myself then,” she said, resting her head in her hand and gazing toward the field. “What’s it like, being wise? I feel like I’ve spent my whole life being the opposite.”

“Everything will work out. It always does,” said Randall, yet as soon as he said it, he knew it couldn’t be true. Nothing worked out really, did it? The appearance of structure was a cage. Those Romantic spirits were right. The tall black stalks of the cornfield, so upright and sure of their positions, marching in rows yet journeying nowhere.

“I wish I could see further,” she said. “What lies beyond the beyond. Tell me how you think.”

“About what?” asked Randall.

“How you think when you think.”

He laughed: “Drinking will do this to us, make us philosophical.”

“Tell me.”

“For me, rooms build themselves around ideas. The planks of floors, walls hung with paintings curling in like fingers into an open palm. My thinking’s like that.”

“What am I doing there, in your rooms?”

“Meaning?”

“I’m there, aren’t I?”

She hadn’t taken her eyes from the line of cornstalks when her hand slid down the front of his pants. Randall bit his lip, then leaned to kiss her. “No,” Rose-Lynn said, her eyes still forward, peering toward some dark distance. It wasn’t at all what he wanted. It was detached, impersonal, and finished quickly, a fulfillment of two bodies inclining themselves toward one another, yet neither willing to live, to give in fully to that moment. When they did look at one another again, he to her, and her to him, it was with a sense of embarrassment of what they’d just made, a longing to return to the before.

“It’s gotten chilly, hasn’t it?” she said.

“It’s late,” Randall admitted, and Rose-Lynn smiled.

Driving, he felt at the tethered end of headlights, the illumined beams pulling him and the car homeward. The idea that’d resembled Rose-Lynn in appearance—which once might have stood gesturing by an open window or elongated on an upholstered chair in one of the rooms of his mind—had vacated, and only the dull hum of the radio found its way in now. It wasn’t a sadness that filled him, arriving home, but something else, a sloppy cousin to joy when Lois greeted him. “Some night?” she asked.

“I didn’t have much. Only a sip,” he laughed. “How was your evening? All quiet here?”

“I was reading,” she said. “Your pajamas are laid out for you.”

“I wish you’d gone with me.”

Rose-Lynn missed class on Tuesday and didn’t stop by his hours that Wednesday. When she appeared the following week, she didn’t cheerily greet him as she usually did, but she didn’t appear upset or bothered. He called on her several times during discussion, found himself complimenting her responses more than he’d compliment other students’, just to let her know that he was still there, with her, despite what’d happened between them.

“Rose-Lynn, can we talk after class?”

“I have somewhere else to be,” she said. And it was like that for those few times after, even as she sat committing words to a blue book during her final exam: she had somewhere else to be. It was John Goodwin who told him later that Rose-Lynn would be transferring to Yale in the fall.

Born in York and raised in Dover, Pennsylvania, Michael Hyde is the author of What Are You Afraid Of?, a book of stories and winner of the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction. His stories have appeared in The Best American Mystery Stories, Austin Chronicle, Bloom, Ontario Review, and Witness. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, graduating with Honors in English, where he studied with writers Diana Cavallo, Gregory Djanikian, and Romulus Linney.