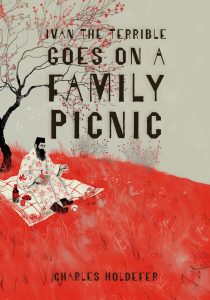

Charles Holdefer is a writer based in Brussels, Belgium. His latest collection of short stories, Ivan the Terrible Goes on a Family Picnic, has just been released. Holdefer’s fiction has won a Pushcart Prize and appeared in The New England Review, Chicago Quarterly Review, North American Review, Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere. He is also the author of six novels. You can find out more about Charles here.

Curtis Smith: Congratulations on your new collection, Ivan the Terrible Goes on a Family Picnic. I really enjoyed it. Not to let the proverbial cat out of the bag, but all of these pieces are about baseball, at least on some level. They take us through the years and across the world. My first question would be, how did this overarching structure/theme come to you? Did you have a few baseball stories already published and then realized you were writing more and more? Or was the idea there from the start?

Charles Holdefer: The structure came to me gradually. In Ivan the Terrible, baseball is a common backdrop, but the stories are very different, and you don’t actually have to care about the sport to get into them. They’re not about “how we won the big game” or some kind of fan fiction. For me, sport is a form of popular theater. Human qualities and problems are dramatized, and it’s the individual character, not the contest, that counts. I tried something similar in my previous book, a novel called Don’t Look at Me, which referred to women’s basketball. It took me some years to pull Ivan together but once I started thinking more historically, the pieces fell into place.

CS: We see different times in history here—(1925 Paris! 1979 Chicago! 1569 Pskov!). Do you use any research/tricks to get your head into those spaces? Perhaps 1979 Chicago was easy, but Bufford County 1899 is a totally different vibe and backdrop—yet you ease your readers into each so deftly.

CH: It’s fun to try on different guises. I’m pretty careful to respect a baseline of accurate information about the twenties or the disco music era or the local team in Hiroshima, but in the end that’s only fact-checking. These stories aren’t “research” or historical fiction in the traditional sense. They’re speculative, sometimes wild and fanciful. Sometimes all it takes is an image, like a facial resemblance between Babe Ruth and Gertrude Stein, and then it’s off to the races.

CS: Yes, I wanted to ask about Gertrude and the Babe. I really enjoy when you bring in historical figures. You had a previous story collection that took on Dick Cheney and his ilk. And here, we get to see this unlikely duo of 1920s icons. I’m guessing you enjoy bringing these folks into your work. Can you address the rewards—and challenges—of using a historical figure in a piece of fiction?

CH: Well, the immediate reward is that I get to bring on stage a character with a ready-made backstory. This allows me to plunge straight into the action, no fussing around. The challenge is that this foreknowledge brings obligations. It should add something; it should matter somehow. If it’s only a cameo by a famous person without contributing to the meaning, then it’s an empty gesture. Here I use Ivan the Terrible to introduce a pastoral idea that gets played out in subsequent stories. This is an opportunistic appropriation that I hope is generative—but it’s definitely not “history.” Ivan is more light-hearted than Dick Cheney in Shorts, which was a darker book.

CS: You’ve been publishing a lot recently—novels and story collections. How do you juggle these projects? Do you work on a novel until a certain point—then take a break and write a cycle of stories? If so, do you have any go-to break points (end of first draft perhaps—or some other milestone in your process)? What benefits does taking a break offer when you return to your novel?

CH: Those are serious questions, but I’m afraid I don’t have a neat answer. I do feel happiest when I’m working, when I’m absorbed in something. But it can be hard, and I get stuck, so I bounce to something else. Then I bounce back. Break points like a first draft, or a fifth draft, are psychologically gratifying when I get there—but I don’t always get there. Publishing is nice when it happens, and I’ve been fortunate, but when a book comes out, due to the time lag, my head is usually somewhere else. I’m most at peace when I’m working.

CS: I liked all the stories here, but my favorites were “Foul” and “Deadball,” and while the book may refer to baseball, these two are really love stories. Do you think love—especially love that doesn’t quite connect—is one of the prominent themes in your work? Fitzgerald said he could only write about a few things—as you look over all that you’ve written, can you identify any central themes/ideas that you keep circling back to?

CH: In earlier drafts, I didn’t consciously set out to write them as love stories but for those examples, yes, that is what emerged, what I had to explore. I was drawn there. As for central themes, that’s a question I would’ve found impossible to answer a number of years ago. But with hindsight, I notice a couple of ideas that keep popping up. The first one: we’re not as smart as we think we are. The second one: we are more free than we usually allow ourselves to be. That’s about all I know.

CS: So let’s talk baseball. What was your favorite season/team? I’m partial to the ‘93 Phillies, but I have to admit the current Phils are pretty entertaining too. Who’s your all-time favorite player?

CH: When I was a little kid, copying my big brother who admired Mickey Mantle, I was intensely interested in the Yankees, which is a bit weird for a rural Midwesterner. But I had to get a divorce from New York during the Steinbrenner years. It got too obnoxious. Since then, I haven’t been particularly loyal to a team, but I still enjoy the show. As for a favorite player: well, it sounds corny, but when we were kids we used to study the backs of baseball cards and take note of the birth dates of players and write them letters with birthday greetings, and some of them responded. One special day a personal reply from Roberto Clemente landed in our mailbox. He’s a player I appreciate even more now, from an adult perspective. He was an impressive person, larger than sport, and I still watch clips of him on YouTube. And the game is not just about its stars; it’s about hard-working journeymen who are now forgotten, guys like Don Wert, who also answered us all those years ago. Thanks, Don!

CS: I really appreciate your tone in the book. There’s a real storyteller vibe going on—the book moves through places and time, but wherever we land, we instantly feel an intimacy with the characters. At this point of your career are you aware of tone—or have you been doing it so long that it comes easily? Another thing I enjoyed was the pacing—and in a way, it felt like a baseball game—unrushed yet full and complete—sometimes soaring and sometimes bittersweet. Was this in your head as well—or am I bringing too much of my current ball-watching frame of mind into this?

CH: Tone is the collision of language and plot, more or less. The shorter flash pieces have less plot and lean more heavily into language. But the longer stories give themselves more time to unfold, the pacing is different, with more events, and yes, perhaps it is baseball-ish. And though there’s some truth to the notion that the game is like life itself, I’d also underline how the limitations of the game compared to life account for much of its appeal. The space is strictly rule-bound and self-contained, and it provides a way to focus. We hunger for such focus in life. This heightened focus can be reproduced in art, and that’s definitely worth trying for.

CS: Loved the Dylan epigraph. What’s your go-to Dylan album?

CH: Not sure I have one, but Bringing It All Back Home has songs like “She Belongs to Me” and some others that have left imprints on my mind like tattoos. They won’t go away. Maybe it’s because of good songs that I’ve never bothered to get tattoos.

CS: What’s next?

CH: I’m immersed in a novel called Bomp that’s more formally challenging than anything I’ve tried before. Still trying to figure out its turns but am enjoying the experience.

Curtis Smith has published over 125 stories and essays. His latest novels are The Magpie’s Return (named one of Kirkus Review’s top indie books of 2020) and The Lost and the Blind (a finalist for Foreword Review’s Best Indie Adult Fiction of 2023). His next novel, Deaf Heaven, will be published in May 2025.