To read Courtney Bambrick’s review of Fractures, click HERE.

Philadelphia Stories: Publishing Local Writers & Artists

To read Courtney Bambrick’s review of Fractures, click HERE.

Some of the feelings within a Black life cannot be easily expressed; they contradict each other. Sometimes a person wants revenge against the oppressing majority, and other times, they seek assimilation. Despite the difficulty of translation, Kirwyn Sutherland’s Jump Ship illustrates the triumphs and torment of Black people in America.

Sutherland is a poet based in Philadelphia. He has published two chapbooks, X: A Mixtape and X: A Mixtape Remastered, has written book reviews for WusGood magazine, and has poetry published by Tobeco Literary Arts Journal, Drunkinamidnightchoir, APIARY, and Public Pool. Jump Ship’s illustrations are by visual artist and DJ Oluwafemi.

Jump Ship reveals the mental conversations Black people have with themselves about difficult subjects. The poem, “The Email Said” shows the hidden frustration Black people have when forced to code-switch. “Assimilation” details the mind and the fixed smile of a man who tries to conform with racist coworkers. “Taunts to the Klan” is a proclamation of pride and glee to spite racists.

Like a mind racing, Sutherland’s poems read quickly. He does this by using slash marks in some poems and all caps in others. “The Email Said” uses repetition to create speed.

talking to the wall about

what you would have said

to the ‘next person

who spoke so well

of your “speak so well”’ (16-17)

In “Assimilation,” Sutherland creates speed with imagery:

When I heard my co-workers say nigger

It almost knocked the whiteness

out of me but I caught it with my

fist and prayed whiteness wouldn’t confuse

the grabbing for a power move (13-15)

“Assimilation” is also notable for its references to pop culture: an epigraph says it is inspired by Sarge from A Soldier’s Story. Another poem in this collection that talks about conformity, “Uncle Tom’s Redux,” calls out Kanye West, Steve Harvey, and others for selling out their Black pride. The references in Jump Ship make it timely and relatable.

“Taunts to the Klan” uses speed similarly to “Assimilation”; both use description to create intense situations. But thematically, the poems conflict. The narrator of “Taunts to the Klan” can spot a closet or a proud racist within seconds, but the narrator of “Assimilation” wishes to fit in with the racists around him, so much so that he maligns his Black co-worker. Black pride and self-doubt, ideas like these are explored in Jump Ship.

Some poems use slash marks as well as line breaks to affect pacing; others use capitalization to affect the volume and intensity of specific words or phrases. Most of the poems manipulate their speed in some way, leading to a reader feeling impassioned. These poems are not contemplative gazes at nature; they’re a door kicked off its hinges. They’re shouts of pride and wails of agony from centuries of torment.

Poems for the Writing: Prompts for Poets (2nd Edition) [Texture Press, 2019]

Review by Jamal H. Goodwin Jr.

Poems for the Writing: Prompts for Poets is more than a motivational tool or instruction manual for a beginner poet. It is a source of joy, insight, melancholy, curiosity, and humor. This variety of emotions arises thanks to poets of various levels, from students to classical poets to professionals. Valerie Fox and Lynn Levin, the authors of Prompts for Poets, contribute poems as well. Fox is a writer who teaches at Drexel University, and Levin is a writer and translator who teaches at Drexel and the University of Pennsylvania.

But this book is more than a writing guide with prompts for poets: it is also a poetry collection. Prompts for Poets offers strong lines, voluble stanzas, and opportunities for both humor and contemplation.

The narrator in Levin’s “Paraclausithryon” ostensibly pleads for entry into a lover’s abode, but is actually castigating them:

I beg news of your dreams

the milk of your voice.

Don’t waste yourself

like an unread book

…

I will wait a year, maybe two

then don’t blame me if I seek

someone simpler

less in need of coaxing.

The scorn of the narrator is palpable, and the ease of their transition from serenading their lover to threatening abandonment is almost disturbing.

Devin Williams’ “Rats” delivers insight on a marginalized soul. The mythology that Williams evokes demonstrates that there is more to a rat. They are not just subway dwellers; rats have admirers, and rats have feelings, too:

I am present when food is abundant.

Companion of Daikoku,

Savior of Sesshu,

First sign of the Zodiac

…

It is only language that separates us.

Yet, you avoid me

And attack me.

You don’t know me,

How can you claim to know how I feel?

Prompts for Poets has humorous, carefree moments too. In chapter 11, “The Advice Column Poem,” desperate readers ask columnists for life advice. Each poem’s columnist gives an absurd answer, one that ignores the question and frequently prompts a laugh. In Lauren Hall’s “Lost without Frank,” a wife inquiring about difficulties with her husband is told by the crystal-ball-consulting Madame Rosa that he does not exist:

You say this Georgina never existed, and there Madame Rosa agrees, but who’s to say that Frank wasn’t just more of the same? Who’s to say you didn’t make him up one afternoon while you were sorting your sock drawer or scrubbing the toilet?

There’s plenty more prompts and poetry to be found in Prompts for Poets. The prompts and instructions are sure to get the mind warmed up and ready to write while the poems bring about contemplation or give rise to a laugh. More can be found on Fox and Levin’s collaborative website, https://poemsforthewriting.com/.

Clauser, Grant. Muddy Dragon on the Road to Heaven. Codhill Press, 2020.

I read once that Sylvia Plath’s original manuscript order for Ariel began with “Love…” and ended with “spring” and that this was intentional and significant (despite being woefully out of step with the mythology that has grown up around her work since her death).

Similarly, Grant Clauser’s Muddy Dragon on the Road to Heaven (winner of the Codhill Press Pauline Uchmanowicz Poetry award) begins, “Lord, forgive us our pessimism…” and ends, “…giving the world all/it can take, light/playing over every/precious thing.” These choices are also clearly significant in terms of the voice Clauser cultivates between these covers.

These are not naïve poems, but they are hopeful. There are times when the voice is wry or even briefly despairing, but they always seem to carefully weigh the natural world and the father’s place in his growing family to find something to rejoice in, as he states in the closing lines of one poem: “how in this life we tell each other/stories to get through the day, to teach/our kids to love something distant/…because it seemed/like the best way to preserve/the time we had, the time we have” (from “Adopting a Manatee”).

These poems build upon the voice and awareness Clauser first explored in Reckless Constellations (his 2018 collection from Cider Press Review). In that collection, the poet’s love and nostaligia for his childhood spent outdoors resonates throughout his poems. In this one, his meditations mourn the coming loss of the natural world from climate change. He also looks to past environmental disasters through the lens of individual creatures, such as the ill-advised dynamiting of a whale carcass on a beach in the 1970s, an “anti-ode” for the spotted lanternfly and the creature who lends her name to the collection, the Muddy Dragon on the Road to Heaven (a fossil discovered in China and thought to be about 66 million years old), who “was beautiful/because even as it died/it was so close to flying.”

Several of the poems make use of Shakespeare or Miltonian lines as their titles, but the trained eye of Clauser’s poems return to the smallest living thing as a telescoping metaphor for our purpose here on the planet as in “Hummingbird,” which previously appeared in the Sugar House Review (wondering in the closing lines, “how dark worlds hidden from sight/can still bend starlight around them”). But the beating heart of the collection is the poem “Men Weeping in Cars,” where Clauser admits, “Maybe life is good after all,/you’ve worked and saved and built/but the color of the sky reminds you/how thin the line is between wanting/and needing, and you tell yourself/not to do this to your heart again.” Trust this poet and his brilliant poems.

Matthews, Airea D. Simulacra. Foreword by Carl Phillips, Yale UP, 2017.

Airea Matthews’ Simulacra doubles then quadruples its mirroring. As the author teases in her Notes, “the [title] derives from the Latin… meaning ‘to make like’ or simulate. …[but], according to [Philosopher Jean] Baudrillard, the simulacrum was that which ‘hides truth’s nonexistence.’” It is clearly this secondary definition that she is playing with in her text: these poems seem to pull back the curtain, revealing a dark mirror or pond that in its brightest spots truly illuminates the show behind us.

The compelling majesty of these poems is that they somehow remain inviting; it would be easy for such complexities to lock out the casual reader. But Matthews draws on a vast literary store of familiar characters (from Ancient Greek mythology and celebrity poets), folding in a modern sensibility that manages to not feel gimmicky. She often uses epigrams from French philosophers and writers (Camus, Baudrillard, Barthes) to remind us of the depth of what she is trying to achieve, even as she drops her characters—some recurring, like Anne Sexton the nurse who has never heard of Anne Sexton the confessional poet—into familiar settings. Matthews uses the operetta and biblical-style verses as easily as she does some more quotidian forms of communication that hardly seem artful (like texting and tweeting), until, in her hands, they become so. The text messages delivered, significantly, out of order—so that the reader must rely on timestamps and numbering to read them in their intended sequence—between poet Anne Sexton and the doomed Arthur Miller character Tituba from The Crucible of “Sexton Texts Tituba From a Bird Sanctuary” could really be titled something along the lines of ‘desire, foreboding, and womanhood.’ Those ideas pulse throughout this collection.

The spine of hunger, longing and trauma runs as an undercurrent through all of these poems, voices, and shifting presentations. As Carl Phillips mentions in his foreword (detailing his decision to select Matthews’ manuscript for the Yale Younger Poets series), “she offers us nothing less than an extended meditation on the multifariousness of desire” (xv). The poet herself remains unknown, even though she uses several characters (like “The Mine Owner’s Wife,” “The Good Dentist’s Wife” and Anne Sexton the poet) as stand-ins for the “I” presence, so that it becomes clear that there is something she finds compelling about women who were limited in their ambition at the hands of their male counterparts. But these are far from “domestic poems,” as some of these titles would have you believe. Matthews’ heroines are powered by their self-awareness, even though they are trapped. Her voice vibrates with the power of the poet Ai, that great master of the dramatic monologue. Matthews seems to be saying that there is power in femaleness that rides the great tide of generations. As she writes in “Select Passages from the Holy Writ of Us,” “They called her morning.5 She misheard mourning.6” This collection is a tour de force in its breadth and depth.

https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300223965/simulacra

By Courtney Bambrick

In her collection Ghosts, Nancy Davis presents a changing and challenging American landscape. Her poetic terrain is in turn at odds and at ease with history and wilderness. The first poem in the collection, “Sanctuary,” offers a glimpse of the layers of earth and time:

the dead are buried here.

contaminated fish bones compressed into

strata of an unintended geological age… (5).

Throughout the collection, we dig through that strata and examine the bones Davis unearths in poems that connect modern living to a pervasive but opaque past:

Like a mole, blind in its star-starved

pursuit of light–a tuberous longing

for air…

**********

Far up the hillside, a mausoleum

of memory haunts. Children play

in the dirt… (“Ghosts” 11).

Setting poems in both domestic and untamed places — gardens, forests, cities — allows Davis to reflect on the interactions of time and place and the uneasy balance between:

in the lake house on the bluff

a woman opens her door

peering out somewhere between

dusk and remembrance… (“Into the Garden: Dreamscape” 17-18).

Davis shows us a land that is as scarred and aching as our own bodies, and as vulnerable. Birth and death are visceral and natural — shocking, but expected. In the garden, for instance, new life may be possible:

…mounds of freshly shredded mulch:

hardwood pining for resurrection,

redemption (18).

While in the poem “Desire” Davis describes a bear, she might be describing the unconscious or the way memory asserts itself unexpectedly and without welcome:

All at once it appeared: barreling out of its musky secrecy,

voracious demeanor, ambling with surprising speed and grace

up the hillside. clawing madly with one massive, capable paw

at the foliage caught in its thick, black pelt (27).

The “invasion” is jarring to the poem’s speaker and to the reader, reminding us of the dangers we don’t often see beyond the edge of our backyards. The bear reminds us of other bears we’ve seen or read about in the news or in fairy tales: “…bear stories circled the valley/like hungry hawks.” They are familiar and foreign, “the most terrifying and exuberant,” and like our memories, they threaten damage, but might pass quietly if we are lucky.

As it expands personal memory to cultural or political memory, the poem “Firestorm: Checagou” connects histories and peoples to the physical earth through work and violence. Industrial and natural imagery vie for attention through the poem as through the collection. The dangers evolve and transform as time passes and the landscape reflects human manipulation.

A clear-eyed and open-hearted reflection on our place in the American landscape, Ghosts helps the reader navigate a relationship with the relentless but fragile natural world and reminds us of our proximity to both danger and safety.

Book Review:

Steve Almond, Bad Stories: What the Hell Just Happened to our Country

By Julia MacDonnell

My urgent advice to anyone who, like me, was stunned, outraged and disoriented by the 2016 election of Donald Trump as president: Read Steve Almond’s “Bad Stories: What the Hell Just Happened to our Country.”

Bad Stories, a slim paperback published by Red Hen Press, is a page-turner for the politically engaged and/or the dazed and confused. It offers no solace for our current civic climate, a country riven by discord, with a corrupt plutocrat and apparent sexual predator (just grab ‘em by the…) occupying the Oval Office. Instead Almond illuminates, with uncommon skill, wit and pungent language, the dark forces in our culture, that, with the precision of a homing device, made all but inevitable the election of a man with “the heart of an autocrat and the mind of a gorilla.”

The titular bad stories, sixteen of them, are, in Almond’s telling, cultural narratives most Americans accept as true. For example, that the United States is a representative democracy or that economic anguish fueled Trumpism. That the Cold War is over and we won, and, echoing loudest from coast to coast in the fall of 2016, nobody would vote for a guy like that!

Almond, the author of three collections of short stories and several books of nonfiction, says that telling stories is what he does best. Hence his focus here on the stories that he believes have gotten us into so much trouble, stories we’ve been telling ourselves and stories that, unchallenged, mass media have been telling us for decades. These ‘bad stories,’ Almond demonstrates, have lately been amped to cacophonous levels but are rarely reflected upon, or their consequences considered. In this book, Almond reflects upon their flaws and considers possible corrections.

Bad Story #3, Our Grievances Matter More Than Our Vulnerabilities, offers a nuanced argument, a keynote for the book. In it Almond describes Trump as a protest candidate who considers traditional politics ‘bullshit.’ He posits that Trump’s base, (generally considered white, male and working class) enflamed by his campaign rhetoric, failed to vote for candidates whose policies might have made possible the job programs, health benefits and housing support they needed to make their lives better. Instead, in anger, they voted against their ‘curdled perceptions of government’ for a man who, so far, has given them nothing except the chance to make noise at rowdy rallies where they get to rail against Fake News and other ‘elites.’

Adding to the horror, feeding it, is the fact that so many Americans don’t vote. Almond offers the familiar stunning data: three million more people voted for Hilary Clinton than for Trump – but only 60 percent of Americans bothered to vote at all. He calls such civic apathy the ‘dark matter’ in a nation ‘overrun by bitter partisanship.’ He argues, convincingly to me, that such apathy is a form of privilege, the privilege of negligence ‘that arises in a population insulated from foreign threat and domestic hardship.’ Learning about the policy proposals of candidates and then voting, he posits, are essential responsibilities for those who value democracy and fear our slide toward fascism.

Almond, who began his career as a newspaper reporter, first in El Paso and then in Miami, is especially perceptive when discussing the role of news media, the so-called Fourth Estate, in the rise of Trumpism. Highlighting cable news, Almond asserts that Trump “became a front-runner because he was treated as a front-runner.”

In story #6, What Amuses Us Can’t Hurt Us, Almond says he wasn’t able to have a serious discussion with friends and acquaintances about the 2016 campaign because “they didn’t take the election seriously.” Almond resurrects Neil Postman’s 1985 screed Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business to show that however damaging the Trump presidency has been to our country, it has, for many, been irresistibly entertaining. That’s why Trump’s version of reality show politics has been a boon for profit-driven news media. He quotes Les Moonves, chief executive of CBS, telling a conference sponsored by Morgan Stanley that the Trump candidacy, “might not be good for America” but “the money is rolling in” and it’s “fun.” (Since the publication of Bad Stories, and following accusations of sexual misconduct by a dozen women, Moonves has stepped down from CBS.)

In #13, There is No Such Thing as Fair and Balanced, Almond deciphers how the dismantling of the Fairness Doctrine during the Reagan administration gave rise to right wing talk radio, the bailiwick of conspiracy theorists and demagogues. The Fairness Doctrine, instituted by the FCC in 1949, required holders of broadcast licenses to offer ‘honest, equitable, and balanced’ coverage of all controversial material. In other words, broadcasters had to tell both sides of the story. But Reagan’s FCC revoked the doctrine, claiming it harmed the public interest because it violated the free speech rights guaranteed by the First Amendment. (Befuddling, to say the least.) From that moment on, in a rightward lurch, the airwaves resounded with the dark visions and loud voices of Michael Savage, Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity and others. While these so-called truth tellers only garbled it, they stoked the grievances of their legions of listeners, and made themselves wealthy and politically powerful. Trump, an early Savage listener, is known to be a huge fan. Hannity now serves as an unofficial presidential advisor.

Like the best essayists, Almond has a well-stocked mind. He deploys it shrewdly in Bad Stories, pulling from his brain shelf works of philosophy, sociology, political science and literature to buttress his points. Among the novels whose words and themes are finely woven through his arguments are Moby Dick, Slaughterhouse Five, Fahrenheit 451, Heart of Darkness, The Great Gatsby, and The Grapes of Wrath. This weaving offers a heartening look at the important stories classic literature has to tell us. If only we paid attention.

Almond also presents, for our examination and amusement, his own failed if prescient novel featuring as protagonist a character named Bucky Dent. Dent was ‘a hedonistic right wing demagogue’ whose code of conduct included ‘manic self-promotion, gluttony, screen addiction, sexual predation and casual racism.’ His attempted novel, Almond says, was inspired by his concerns about the Tea Party’s fundamentalism. But it failed, he writes, because he fell out of love with his own creation and because his early readers found Dent too ‘cruel and cartoonish’ to be believed.

Almond calls Bad Stories ‘a rhetorical panic room.’ I don’t disagree but it is much more than that. It’s an enthralling examination of our disastrous current politics, replete with Almond’s impressive research as well as his signature wit and vibrant language. Moreover, Bad Stories, as it delves into Almond’s personal history, and his self-described failure as a reporter – his editors always wanted ‘indictments’ whereas as he wanted to find out ‘what it meant to be human’ –can also be read as the evolution of an important American writer, one who eschews the role of pundit. Instead, Almond has chosen to become an interlocutor of the culture, one who hopes with his ideas and his words to generate conversations and maybe to prompt action. The role of interlocutor is what links Almond’s fiction with his nonfiction with his podcasts with his teaching and with all of his other work. Always he is seeking to answer a single question: What does it mean to be human?

By the time I closed Bad Stories for the second time, having underlined and highlighted its pages almost into oblivion, hope glimmered on the horizon. I understood better than I ever had why and how we’ve arrived in this broken place and what I, Citizen Me, solo voter, have to do to get the humanistic democracy I need and want.

Julia MacDonnell (Chang) has lived many lives, among them, urban homesteader, circus performer, modern dancer, waitress, anti-war activist, newspaper reporter, college professor, and ‘gluer’ of velvet boxes on a production line in a rosary bead factory. MacDonnell’s second novel, Mimi Malloy, At Last!, was published by Picador in 2014, and chosen as an Indie Next selection by the A.B.A. It was released in paperback in 2015. Her first novel, A Year of Favor, was published by William Morrow & Co. Her stories and essays have appeared in Ruminate, Alaska Quarterly Review, North Dakota Quarterly and many other publications. She is the former nonfiction editor of Philadelphia Stories.

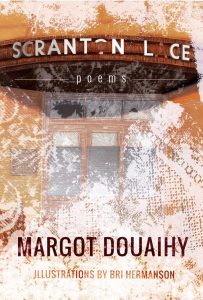

Review of Scranton Lace: Poems (Clemson University Press)

A lyrical and brutal dismantling

by Emma Murray

“In Vulgar Latin, Lace means entice, / ensnare.” Poet Margot Douaihy and scratchboard illustrator Bri Hermanson do just that with Scranton Lace: Poems. Douaihy’s poems lyrically and brutally dissect coming of age as a queer person in the Rust Belt, and the Scranton Lace Company—a hometown fixture turned ruin—is her muse. From sleeping off a first hangover in “The Lace” parking lot, to falling “in lust” with a diner waitress who worked nearby, this fixture and the lace itself serve as portals through which Douaihy conjures and reconciles her adolescent homophobia, as well as what it means when these familiar structures falter. “Like a honeycomb, the more you turn a memory / the more doors you find.”

Not only is this collection a tour de force lyrically, but also visually. Hermanson’s signature scratchboard illustrations guide the reader through interludes about two imagined female factory workers. Hermanson’s medium seems symbolic of the collection’s intent—etching away literal and figurative edifice to get to the raw wound. This, combined with how Hermanson has dappled pages with relief prints of genuine Scranton Lace, will leave readers fingering the pages for more. But don’t let the enticing lace fool you—this collection has teeth, as Douaihy reminds: “yes lace is porous / but it can still smother.”

Poet and visual artist Emma Murray received her MFA from Oklahoma State University. She received an Academy of American Poets Prize in 2016.

MORE INFO

Purchase Link: tinyurl.com/ScrantonLace

Watch the book trailer: https://vimeo.com/259487376

The Origin of Doubt, Nathan Alling Long’s glorious debut collection of short fictions, is dedicated ‘to those who don’t quite fit in.’ Its fifty stories, some no more than a paragraph long, could serve as a missal for a vast congregation of outcasts and wanderers; angst-ridden adolescents, erotic explorers, and philosophical self-searchers.

These stories – most would be called flash fiction due to their brevity and obsession with ‘moments’ of experience – offer highly nuanced meditations on sexual awakening and its confusions, eternal parent/child conflicts, sibling connections and their opposite, romantic love and its impossibilities — and Long’s stunning imagery weaves them into a radiant mosaic. For The Origin of Doubt is, above all, a contemporary mosaic, a post-modern one, spangled with a pure and at times enthralling take on same sex love and its hetero counterpart, not to mention several other life and death matters. Its protagonists, passionate and yearning, are so profoundly ‘there’ in their fictive worlds, be they Muslim prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, young seekers in a Thai monastery, or any of a score of other possibilities, that they pull the reader in close for an embrace, or, at times, a death grip. Like all of the best fiction, Long’s stories takes readers places they never planned to go, and surprise them with the unforeseen pleasures to be had after their arrival.

Taro, one of the longer stories, examines the deep connection and subsequent disconnection of two brothers. During childhood, they fight, they wrestle, an endless competition, and Taro, the older, always wins. One day, the family is moving, and the boys, in a joke played by the movers, end up rolled up together in a Persian carpet, a dark and airless space where, the narrator says, he’d be happy to die. “I felt myself pressing, not down into the earth, but up against the weight of his body, to feel it more. …this was all I wanted – not to be him, but to be against him, just as we were.”

It is said that flash fiction suits perfectly an age of short attention spans; readers who long for a quick hit and then move on to their next diversion. Long’s work may undermine that belief if only because his stories, intense and sensual, demand repeated reading. Like prayers, they trigger reflection, and the desire to go back again through the words. With repetition, these stories offer up more of their gifts. Some, like When My Mother Died, might be called prose poems. In it, the genderless narrator says, “A thousand bottles of red wine flowed across the living room floor, and I felt the miscarriage begin, of the child I’d been carrying my entire life.” Others, such as Jealousy, Buried, Sweeping, and How to Bury Your Dog, might be considered parables. Whatever genre basket they’re dropped into – Long’s work defies them all – their impact far outweighs their word count

Long’s characters, sometimes named but often not, share the burden of being alive in a splendid but confounding world, a world in which urgent questions go unanswered, but experience itself creates an irresistible thrum. Many remain spiritual long after they have fallen away from an organized religion. In this world, love is, more often than not, “peculiar and unchained- like a neglected yard dog. It can bite you more than once. It can bite you in different places.” It’s a world in which summer buzzes ‘like neon,’ the moon sneaks in over sleeping faces ‘the way a moth might glide across your arm,’ the earth can be ‘wet as a tongue,’ and ‘conversation surfaces once in a while, like a whale coming up for air, then disappears.’

The collection, published by the venerable Press 53 of Winston-Salem, is divided into three sections, The Origin of Doubt, A House Divided and The Fortunate. Read in order, these sections create an arc of a storyteller’s coming of age. But because the storyteller is a shape-shifter with many guises, and the stories are told in many styles and from many points of view, the arc reveals itself only gradually. In an early story, Between, a befuddled young boy visits his father in prison and asks him about the word ‘conviction,’ a query the father answers but not in the way the boy had hoped for. “Before the next month was up, I would forget his face, forget almost, that he was my father.” In the collection’s penultimate story, Sweeping, the narrator opines, “My life is not without purpose…We sweep each day, that the world may be – not clean exactly, never clean – but cleaner: And that is enough.

Yet The Origin of Doubt, doesn’t require orderly reading. You can open the book on any page and be certain to find a reward: a puzzle, a provocation, a delight, a question asked but left unanswered. Long, a professor at Stockton University in Galloway Township, N.J., has said these stories were culled from about 15 years of his writing. All but two have been published in such publications as Atticus, Clackamas, Indiana Review, Story Quarterly, Fringe and Salt Hill. Gathered together, they generate a synergy of themes, and their heft promises more compelling work to come from Long. In Portraits of a Woman the omniscient narrator reflects “…she knows this character is from another century, as no one, these days, looks out a window for quite so long, considers their life so seriously, so existentially, as she is now.” This expresses – however ironically, given The Origin of Doubt’s contemporary concerns – the depth and significance of this beautifully wrought and generous book.

************

Here is an excerpt, a complete story:

Fireflies

At nineteen, he loved Michael who’d made them two flashlights that blinked in a specific pattern, like fireflies. “So we can find each other in the dark,” Michael had said.

But they’d since broken up. Years had passed. They moved to different cities, in different states. He became a teacher, Michael a pilot.

Still, on nights when planes flew overhead, he turned the flashlight on and pointed it at the sky.

Emily Rose Cole won the 2014 Sandy Crimmins National Prize in Poetry for the poem “Self-Portrait as Rapunzel,” selected by judge Jeffrey Ethan Lee. Her poem considers the relationship between Rapunzel and her mother and how a person accepts or rejects various aspects of abuse or isolation because of the attention or even affection that might accompany them. The poem, included in her new chapbook as “Rapunzel Learns to Build,” is startling and delicate, but with a deep resolve and grit at its core. Cole’s Love & a Loaded Gun approaches many familiar characters in unfamiliar states of resignation and agitation. These poems force the reader to reevaluate expectations and assumptions about the figures we like to think we know.

While the premise of the collection suggests Anne Sexton’s Transformations, the figures treated throughout the collection come from all manner of sources; only Rapunzel is shared among the Grimms, Sexton, and Cole. The remainder of the poems concern figures from myth and fable, but also comic books, film, and video games — media that are literally two dimensional in their presentation of characters. Flat characters in our shared stories allow audiences to tailor characters to best speak to or for themselves. Here, Emily Rose Cole shows us what she has brought of herself to these characters: wit, rage, and tensile strength.

A shared quality in many of these poems is the characters’ emergence from a few significant male shadows: those of King Arthur, Clyde Barrow, Superman, Zeus, or Mario (the video game plumber). No longer diminished by their male counterparts, Cole’s speakers often express anger at, awareness of, or frustration with their situations — and the men that accompany or abandon them. Tellingly, the collection is dedicated to “every… woman who’s ever been made to keep her mouth shut.” We cannot ignore these long-silent voices, Cole tells us again and again.

These poems reveal secrets about the characters that sometimes illuminate and sometimes complicate their sources — often the poems do both. The title of the collection comes from the final poem, “Black Widow Explains.” In it, Natasha Romanoff shares her history and shrugs off any interest the reader has in her work. She tells us that there is no real trick: “It’s not hard to be a spy. All women are made of muscle / and trauma.” The speaker tells the reader how to use sexuality to subvert and exploit expectations. Her offhanded manner suggests that her work exists on a continuum that most women find themselves on at various points for various reasons.

Cole reminds us that women often approach challenges differently from men. In her poem, “Your Princess Leaves the Castle,” Mario’s damsel in distress, Princess Peach vents:

For years you’ve solved every problem

by stepping on it. It’s simple for you: pulverize

the henchmen, emasculate the boss, watch me

swoon. Well, joke’s on you, Mario. I quit.

Lois Lane and Guinevere reveal bedroom secrets that show their somewhat magical or alien lovers as more human than not. Leda, after being raped by Zeus in the form of a swan, decides to leave town and “pursue a new hobby: take a shotgun / to the edge of a lake and shoot at every shadow of wings.” The anger and frustration these characters express, being beholden to predictable too-familiar men, is felt throughout the collection.

Though we may have originally found these characters supporting more familiar figures in stories, they have a great deal to say for themselves. They finally defy and emerge from the flatness of the page or screen to speak. Emily Rose Cole recognizes how important the teller of the story can be, and in Love & a Loaded Gun, she brings her own savvy gusto to these compelling voices. In providing such deep interiors for these characters, she forces the reader to look around at other stories and the other characters not examined here. How many flat, unconsidered female characters still have stories to share?