Lost Novella

by Stephen St. Francis Decky

In 2004 I stopped reading books. I had just stopped smoking. I’d stopped smoking because I’d nearly completed writing a novella when my laptop sputtered and died. The data, despite some effort, was unrecoverable. I grieved like someone dear had died.

I’d been smoking since I was a Junior in high school. At that time, I was homeless; In a rare fit of mercy, my dad had kicked me out of his house that summer. Which left me free. But homeless. I spent the first night in a blur in the woods with a fire and some people I didn’t know. I was free, and lost, and after a week, going through some sort of withdrawal from the anti-depression meds I’d left home without. That home had become a pressure-cooker of threats and hostility. There was no going back.

Instead, I stopped at a convenience store in Woodbury, New Jersey and for the first time in my life bought a pack of cigarettes. I lit one up outside. The jitters and withdrawal pangs softened in seconds; the relief was immediate and palpable. As the fog of anxiety faded, I sat down on the curb, opened a notebook, and began to write.

I smoked for 19 years. I’d been writing stories and painting and drawing since I was a child. But the smoking was to my fiction like canned spinach to Popeye: instant confidence and focus. I wrote obsessively, I made it a habit. I smoked upwards of 2 packs a day.

Later I published a couple short stories. They went nowhere but it didn’t matter because I hadn’t written my best piece yet. That one was still coming, and when it came, at the height of its formation – mid-delivery – it vanished.

Smoking did little to numb the despair. I’d begun seeing its effects in the mirror as well: I looked very mid-30’s, smoker. This visual prompted me to take a day off from smoking. In the 19 years I’d been smoking I’d never gone an entire day without a cigarette. But I was going to take a day off. 24 hours. Instead of smoking I would eat cookies and ice cream and drink martinis and pretty much devour anything I craved except cigarettes.

That night I drank 4 and a half martinis. I woke up the next morning on the floor beside my bed. I felt bludgeoned but ecstatic: I’d just gone an entire day without a cigarette. I figured I’d wait a few hours and then have a smoke and a cup of coffee and resume my life. But mid-afternoon passed and evening arrived and I wondered what would happen if I somehow found the audacity to try the martini trick again.

It worked: I woke up the next day in my underwear on the porch, 48 hours smoke-free. It felt like the fabric of my life had been ripped. That’s how I quit smoking.

Eight months later, the pack I’d been working on when I quit was still in my backpack – a subconscious Emergency Kit – with 11 unsmoked cigarettes inside. I remembered this as I was leaving a convenience store on King Street in Northampton, Massachusetts. Embarrassed, I pulled the pack – Marlboro Reds, the ultimate sellout – out of my bag and tossed it into a trash can.

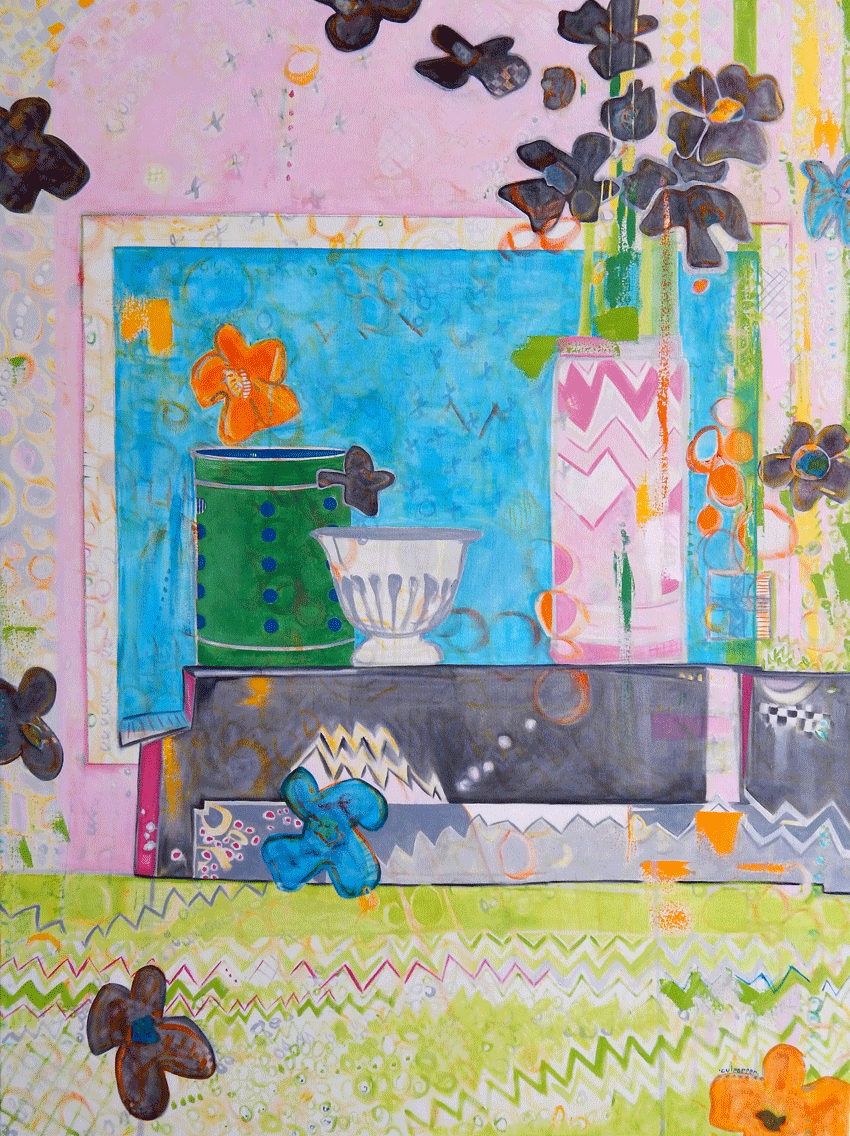

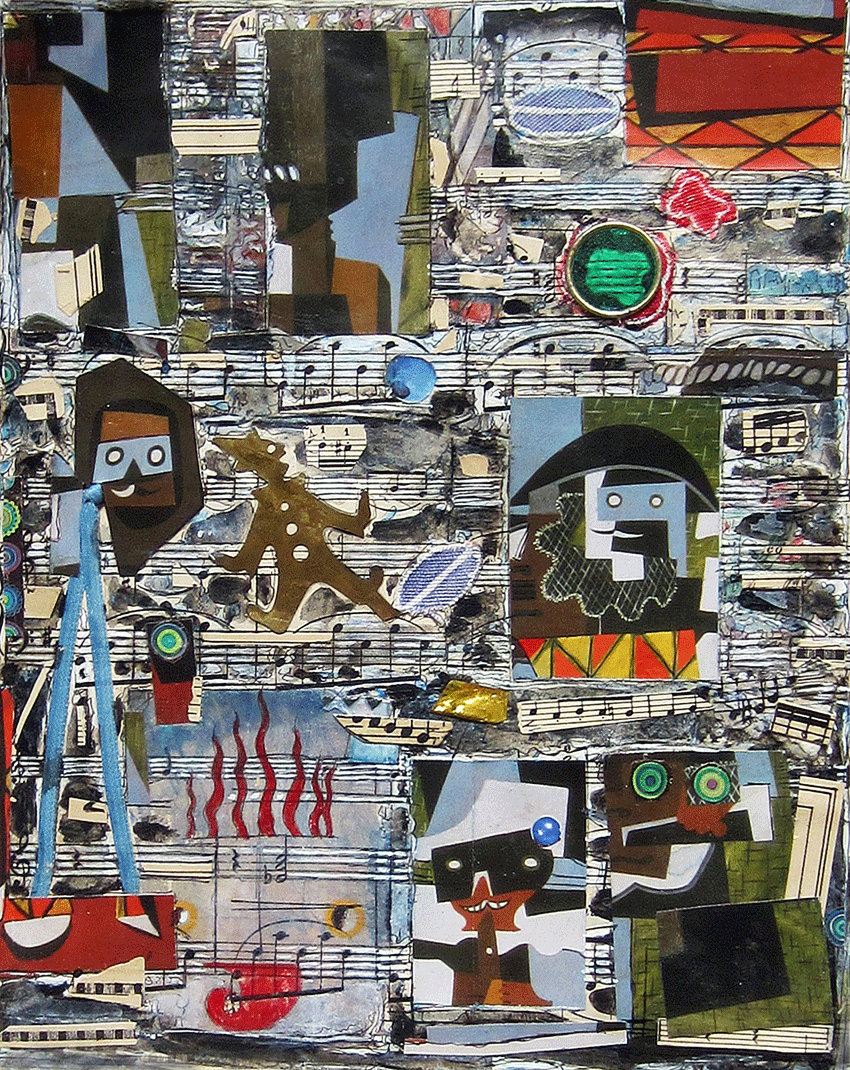

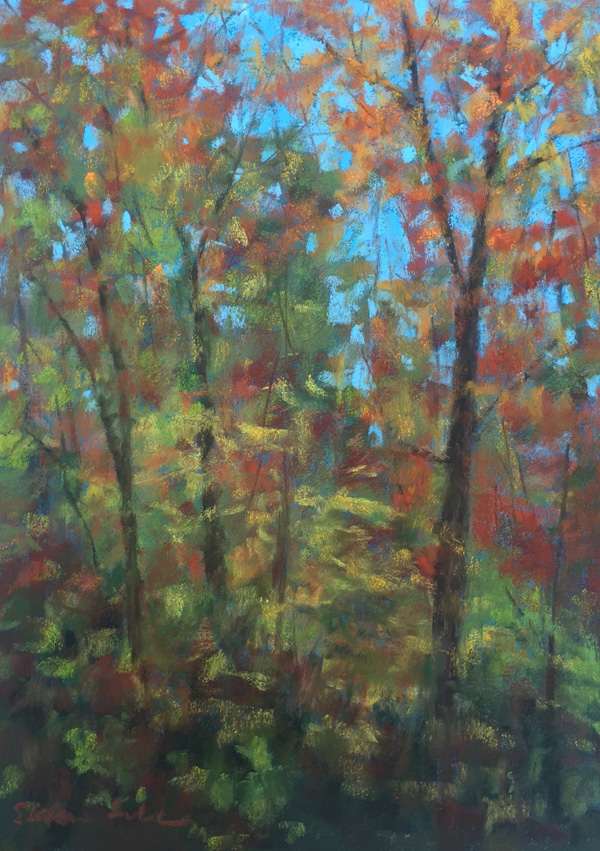

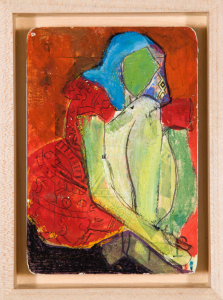

During the aforementioned 8-month contingency period, I climbed Mt. Washington in less than 2 hours, did upwards of 300 push-ups daily, and started painting with renewed energy. I’d never painted with a purpose or audience but I could feel the possibility of one forming. Images began replacing text in my creative workflow. My written output dwindled until I was left with little more than Beckett-like, self-subsuming paragraphs of anti-fiction. The great novella was lost, and in its wake, my writing had become the literary equivalent of autolyzed yeast.

A side-effect of not writing was a burgeoning inability to read long-form works, i.e. books. The two processes had somehow been intertwined, and I was finding it impossible to focus on either. It was deeply worrisome, as I’d been a voracious reader for many years, and a battle at the intersection of inspiration and creativity seemed to be waging inside me.

At a bookstore in Philadelphia, I found and purchased a copy of Albert Camus’ L’Etranger in the original French. I’d studied French in high school and retained some knowledge with occasional tutors, but reading literature en français was a new and suddenly necessary challenge: It forced me to concentrate at a level that had become second-nature in English, and the constant need to check my stack of French-English dictionaries satisfied – albeit faintly – the now-missing physical and gestural aspect of smoking.

I finished l’Etranger, some grossly pretentious Sartre plays, then le Deuxieme Sexe, all with a slowly increasing sense of ease. Later that year I travelled to France and found a copy of Le Tour de la France par Deux Enfants in Lyon, a Marivaux compendium in Chamonix, something by Nathalie Sarraute in Nice. I could understand Molière and Colette but couldn’t keep up with anything modern: My comprehensive abilities were antiquated, and I developed a ready-made excuse in my perpetually-lagging conversational French:

– Je parle comme un enfant parce’que je pense comme un enfant en français

(I speak like a kid ‘cuz I think like a kid in French)

Over the next 12 years, the only books I read in English were Houellebecq translations and systematically timed re-readings of Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle. I read Marguerite Duras, Radiguet, La Fontaine and others in the original French, but with the sense I’d been trapped in a Robbe-Grillet loop of limited literary mobility.

Early in 2017, while recovering from surgery – and as if loosed from a longstanding fog – I began writing again: Mostly short and spastic stories and eruptions, but enough to open the door to reading in English again. It started with Marc Augé’s Everyone Dies Young, then Ariel Goldberg’s The Estrangement Principle. I re-discovered Nawel El-Sawaadi’s Woman at Point Zero, then the suddenly/weirdly inspirational Cicero, then old favorites like Angela Carter, Mohammed Mrabet, Zora Neale Thurston, etc.

I started listening to audiobooks as well. While they were clunky and rare in 2004, they’ve become both accessibile and abundant in the interim, often reaching true eloquence. Listening to Ta-Nehisi Coates reading his own Between the World and Me after the chorus of voices reciting George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo was deeply revelatory.

Still, there’s nothing like the presence of a book, and that physicality lingers in perpetuity: I can almost feel the de Beauvoir text I bought in Geneva early last summer and lost on the Broad Street Line in Philly; that copy of Le Tour de la France from Lyon still rests on my desk, ever-visible from the corner of my eye.

It’s been nearly 15 years since I quit smoking. I stopped taking prescription anti-anxiety and depression medications soon after. At that time, I felt – fleetingly – freed from the narcosis of short, long-term, and acceptable addictions. A slow-building ecstasy of heightened mental clarity whisked away many of the fears and worries that had been stifling my confidence since my earliest years. It was obvious, though, even as it was coursing through me, that the ecstasy wouldn’t last; The feeling itself was strained by an array of side-effects, but like the addictions – and later, the literary anomalies – these eventually subsided, shifting from the harrowing insistence of the present to the fading but temporal archive of memory.

The novella is now but a blip in a long line of lost plans and ideas, but its influence on my story has been manifold. The future may have changed many times over, but I’ve learned that the potential for new creative prospects – even if temporarily obscured – is always there in some way, shape or form.

Stephen St. Francis Decky is a multi-media artist and writer whose paintings and films have appeared in festivals, collections, and museums both nationally and internationally, including The New Britain Museum of American Art and The Museum of Fine Arts, Nagoya, Japan. He has taught Animation and Digital Media classes at several schools, including Tufts University, Moore College of Art and Design, and Lycoming College. As a technical consultant and collaborator, he has worked on multi-channel video installations in Boston, New York City and Montana. Stephen received his MFA from Tufts University and The School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and currently lives and works in Philadelphia, PA.