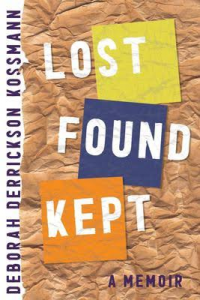

Deborah Derrickson Kossmann won Trio House Press’s inaugural 2023 Aurora Polaris Creative Nonfiction Award for LOST FOUND KEPT: A MEMOIR (January 2025). Book Pages named it one of the Best Memoirs of 2025. Her essays, feature articles and poetry have appeared in The New York Times, Bellevue Literary Review, Nashville Review, Memoir Monday, Psychotherapy Networker and PSYCHE to name a few. Deb is a clinical psychologist who lives in Havertown, PA. For more info: http://lostfoundkept.com

Review By Jennifer Rivera

Deborah Derrickson Kossmann’s Lost, Found, Kept is an exceptional memoir that blends unflinching honesty with such tenderness that you come away not only knowing the author’s story but feeling it in your bones. At its surface, this is a book about confronting a parent’s compulsive hoarding and all the logistical, financial, and emotional chaos that comes with it. But beneath that is something far richer: a layered exploration of love, family bonds, boundaries, and the objects, both literal and symbolic, that tether us to our histories.

From the opening pages, Kossmann draws us into her dual role as both a clinical psychologist and a daughter caught in an intricate web of loyalty and frustration. She doesn’t shy away from showing the reader the grim realities of her mother’s home: the overgrown yard, the blocked windows, the absence of running water, but she never reduces her mother to her illness. Instead, she paints her as a multifaceted, often witty, sometimes infuriating, but ultimately human figure who shaped Kossmann’s life in profound ways. This balance between exposing hard truths and maintaining compassion is one of the memoir’s greatest strengths.

The book is divided into three sections, “Lost,” “Found,” and “Kept,” which reflect the arc of Kossmann’s emotional and practical journey. In “Lost,” we get vivid childhood recollections from growing up in Cherry Hill, New Jersey, to the move from one house to another, and the complicated dynamics with her father, stepfather, and sister. Kossmann’s vividly described details bring these memories to life, whether it’s the smell of her mother’s Wind Song perfume or the exact shade of pink shag carpeting in her teenage bedroom. These scenes not only ground the reader in time and place but also reveal the roots of the family patterns that later manifest in the hoarded home.

In “Found,” Kossmann shifts into the present-day urgency of managing her mother’s unraveling situation. Here, the memoir takes on the rhythm of a real-time crisis, as she and her sister navigate unpaid bills, disconnected phones, and long-shut-off utilities. Her professional training as a psychologist helps her maintain a certain level of calm, but Kossmann doesn’t hide the toll it takes. She finds humor in these moments, too, a dry, knowing wit that keeps the narrative buoyant even though the circumstances are grim.

“Kept” is arguably the most moving section, in which Kossmann reflects on what’s worth holding onto. Not just in terms of physical belongings, but also memories, values, and relationships. She takes inventory of the items from her mother’s house that matter to her: childhood photographs, a four-poster bed, family jewelry, and pieces of art with personal history. These tangible keepsakes become metaphors for the emotional throughlines of the memoir. In choosing what to preserve, she models for the reader how to honor the past without being consumed by it.

What makes Lost Found Kept especially compelling is Kossmann’s narrative voice. She writes with a kind of intimate clarity that makes the reader feel trusted, as though they’ve been invited not only into the family’s living room, but into the guarded spaces where family stories are kept under lock and key. Her prose is graceful but never flowery, sharp when it needs to be, and suffused with empathy even when her patience is tested.

While hoarding has been examined in popular culture, often with a sensationalist or voyeuristic lens, Kossmann’s memoir refuses to exploit. Instead, it offers a rare and humane perspective that acknowledges the pain of mental illness while still recognizing the agency and dignity of the person living with it. She doesn’t pretend that love makes the cleanup easier, nor does she suggest that resolution is neat or complete. Instead, she leaves space for the reader to sit with the mess, both the physical disorder and the emotional turmoil, to appreciate the strength required to face it.

The final pages of Lost Found Kept leave the reader with a quiet sense of hope. Not from a tidy fairy-tale ending, but a steadier kind born from doing the hard work of showing up, setting boundaries, and choosing what to carry forward. The memoir lingers, not just for its story but for the way it challenges the reader to reflect on their own “lost,” “found,” and “kept.” What people, places, and possessions define us.

Deborah Derrickson Kossmann has crafted a memoir that is at once deeply personal and universally resonant. It’s about hoarding, yes, but it’s also about survival, forgiveness, and the enduring threads of connection between a mother and daughter. Honest without being cruel, emotional without tipping into sentimentality, Lost Found Kept is a beautifully written testament to the idea that in the wreckage of the past, there are still treasures to be found.

Jennifer Rivera is a Latina writer and certified dog trainer. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from Monmouth University in May 2024. Her prose and poetry have been featured in The Monmouth Review.