Review By: John Sweeder

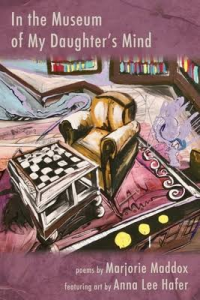

Majorie Maddox’s chapbook, The Museum of My Daughter’s Mind, is a collection of 34 ekphrastic poems that were originally inspired by the author’s 2018 visit with her studio-artist daughter, Anna Lee Hafter, to Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum’s (AVAM) exhibition entitled The Great Mystery Show. Influenced by her daughter’s subsequent artwork, Maddox features 18 of Anna Lee’s surrealistic paintings as well as the mixed media, photographs, and paintings of six other contributing artists, several of whose works have also appeared in the AVAM.

Maddox’s poetry explores the themes of positive human relationships, both interpersonal and intrapersonal, as well as the significance of imagination and creativity, improvisation, memory, nostalgia, grief, isolation, and alienation. Incorporating many of the repeated images contained in eighteen of her daughter’s surrealist paintings, Maddox embeds visual symbols—often numbers and letters, words and brief phrases, as well as concrete images and symbols such as chairs, chessboards and sunlight into her poetry, thus melding visual art with poetic language in an emotive symbiotic dance to deepen illustration her relationship with her daughter’s creative process.

In her pantoum, “The Choice,” Maddox uses her daughter’s visual metaphor contained in Hafter’s painting entitled “The Library” to explore one’s intuitive imagination using bibliographic tools—books, bookcases, floors, and ceilings—to seek truth, “The ancient why of creation”—all the while purporting that there is no set path to take in the pursuit of knowledge since we, “hold the pen and paintbrush” to create our own “Open Sesames.” The poem’s narrator further proposes that we not fret about making poor decisions since “splatter[s are] choices, not… mistake[s].”

In “High Top” Maddox, responds to her daughter’s surrealistic painting of the same name. Both artist and poet engage in an imaginary conversation as if seated across from one another in empty chairs separated by a table and chessboard, all of which are precariously balanced upon a seesaw, a “compass-needle pole.” The narrator-poet-mother asks her daughter: “Are we still we in this unseen grief/that keeps trying/ to listen to soul/ and scream?” Anna responds with her metaphorical “King’s Pawn Opening.” The two opponents in this fantasy chess match are unsettled for the moment, suggesting an estranged relationship. Yet, because of their long family history (“knee-deep in nostalgia”), a reproachment has begun: Mother “can almost see [her] breath;/ daughter “can almost touch [her] words.” Their unspoken grief remains on the table unresolved; however, both are “waiting for [each other’s] next moves.”

A lighter, more optimistic tone is struck in Maddox’s poem, “Sun on South Street.” In this straightforward pantoum, the narrator enables us to imagine what life is like living in a “small quiet room” in a “Big busy city.” Exploring the contrasting themes of isolation versus “camaraderie” and light versus “dark,” we learn that days can be “brightened by the waves of strangers,” “the neighborly sun,” and “outside flowers” on balconies displayed for all to enjoy.

Hafer’s painting, “The Letter E” is an abstract tribute to the creative, right-brained random learner who does not “absorb new information” in a rigid sequential manner. Maddox adapts the theme of her daughter’s work to create an ironic poem of the same name whose narrator morphs into the didactic elementary school teacher we all recognize, the anachronistic school marm who proclaims, “Creativity’s the one transgression/ I won’t allow,” further arguing that curiosity and extraneous questions are no more than “time-wasting, silly digressions…[and] enemies of order.”

Maddox is inspired by the “tender but unsettling portrait” of a pig-tailed pre-pubescent girl holding a black cat, painted by Margaret Munz-Losch. In Maddox’s poem, “Black Cat,” a third-person omniscient narrator tells us that we, as unwanted voyeurs (perhaps the girl’s parents), enter her “stark room.” The anthropomorphized cat she cradles in her arms stares at us with its “bright feline eyes” thinking she doesn’t want us there. The girl’s dull skin squirms like a “pattern of maggots,” her eyebrows are perched like flies above her “dead-sea eyes,” and her tied-up hair is uncombed — all of which the narrator tells us we “cannot see.” These imagined attributes are symbolic of the alienation that many young preteens experience—that is, they want (and maybe need) their own space to develop and mature. Thus, in the lives of young tweens we adults become as welcome as an “infested larvae of plague” hatching into them.

Maddox’s final poem, a sestina with the oxymoronic title, “Wild Rest,” was inspired by her daughter’s painting of the same name. In this work, the narrator begins by posing and answering the following question, “What does it mean to rest…in “a world so wild?” Maddox claims that through daily measured breathing, relaxed contemplation in a “well-worn chair,” and reliance upon our imagination, we should let our mind “wander out amidst the trees.” By exploring a “paradox of renewal,” we learn that “passive breezes [can] become wind” and that “rest [can become] a carnival tour of the spontaneous,” replete with roller coaster rides, fun houses, and Whack-a-Mole games. Maddox wants us to “Be still and know” and recognize “that breath and wind are cousins.”

As careful readers of literature, we are drawn to Maddox’s chapbook for a few reasons. First, we readily identify with her motivation in creating this work. In her book’s introduction, “Entering the Gallery,” she tells us directly that she is “looking to escape [her] fears” of dying prematurely from heart disease and wants to spend the remaining time she has left with her daughter. Many of us identify with this sense of urgency in reconnecting with loved ones while we still can. Time is both short and precious. Next, like Maddox and her daughter, we too enjoy visiting art museums, even small, intimate ones that may contain only a modest number of paintings like the ones in this chapbook. But when art and poetry challenge us to look and read more closely, when art and poetry become melded together, our aesthetic experience is enhanced. Through Maddox’s skill in creating the impressive array of interpretive poetry contained in this collection—poetry that ranges from free verse to sestina, poetry that utilizes the evocative tools of sensory imagery, metaphor, repetition, alliteration, internal and end rhyme—we want to seek out more of her work, and trust that she remains with us for years to come, continuing to engage creatively with her artful daughter, carrying on the centuries-old tradition of ekphrastic poetry.

John Sweeder